After we concluded our epic Branson adventure, Dan and I headed to Kansas City, Mo., to see the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, which also houses the American Jazz Museum in a connected wing.

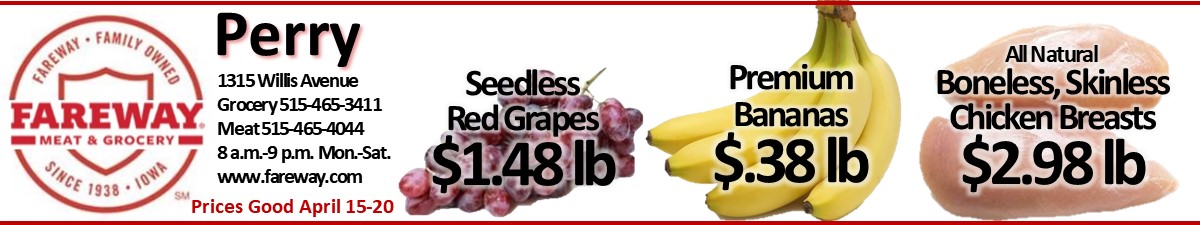

Tickets to both museums were only $15.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum are located on 18th and Vine streets in an old part of Kansas City. The area resembled downtown Perry. It appeared that most of the retail buildings in this area were empty.

Interestingly, the windows of most of the buildings were painted to represent what stores were there in its heyday. We had to parallel park on the street.

The two museums were located in an old building that had been renovated. The American Jazz Museum appeared to be a local cultural center. A group of well dressed people was being led on a guided tour while we were there and shown around the entire complex. There was also an art display at this location.

Major League Baseball was racially segregated until 1947, when Jackie Robinson became the first African-American player signed to play in the white leagues. Robinson played for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was soon followed by Larry Doby, who signed with the Cleveland Indians.

The museum focused on the history of the Negro Leagues, which functioned from 1920 until 1951, when African-American players were regularly being signed by the major league teams, and there was no need for segregated teams.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum contained mostly hundreds of short articles on the history of the leagues and earlier attempts to form a black league. There were also a small display of uniforms from the various teams and a few other artifacts.

You were not supposed to photograph in the museum, but there was not a whole lot to photograph. This was a place that you had to spend time reading things and certainly not a place for kids until they are old enough to read and understand the articles.

It was interesting to view the history of this league and the times that it reflects. It reminded me of the racial beliefs of the older people that I grew up around. A lot has changed over time.

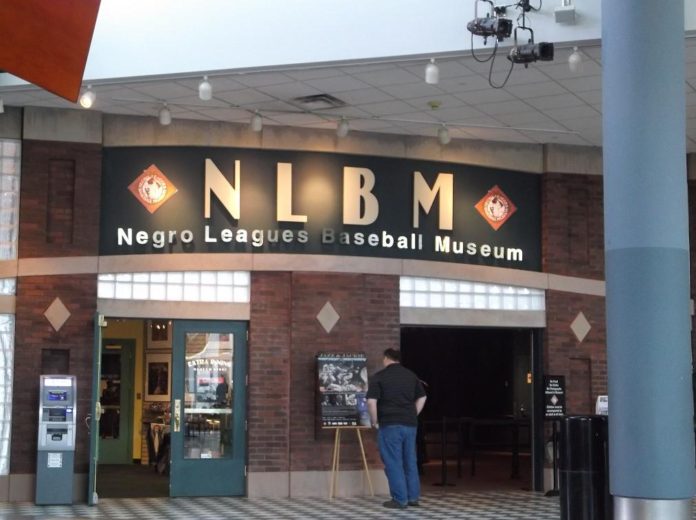

The American Jazz Museum was a small museum dedicated to a few famous jazz artists, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington and Ella Fitgerald. There were stations where you could hear recordings of the featured artists and read information about them and displays that focused on jazz chords and music.

During our visit there was a jazz band playing in a section of the complex designed for this purpose.

The lady working in the museum was very familiar with Des Moines and Perry and excited that we were visiting the museum.

There was a section that showed short videos of jazz bands from the 1930s and 1940s. They were used for video jukeboxes in the ’30s and ’40s.

I particularly enjoyed the section on Louis Armstrong. Former Perry resident Roy Whyte used to tell me stories about his dealings with Armstrong, whom he always referred to as “Pops.” Whyte was only six years younger than Armstrong.

The Hotel Pattee has a room dedicated to Armstrong and his stay there after playing at Lake Robbins in the 1960s. The late Bill Graney told me once that Armstrong was not allowed to stay at the hotel in the 1940s because of his race. Later this changed.

I have been familiar with a few of Armstrong’s songs. When I was in high school, I discovered his “St. James Infirmary.” A slow, sad song apparently about the death of the singer’s girlfriend. I also knew “Hello, Dolly” and “Mack the Knife.”

Armstrong’s 1967 recording of “What a Wonderful World” became a hit again in 1988 when used in the movie “Hello, Vietnam.” Armstrong had died 17 years before.

As a kid I remember seeing him on TV in Mae West’s 1937 film, “Every Day’s a Holiday,” and more recently I saw him on reruns of the “Flip Wilson Show.”

Armstrong was a legend starting in the 1920s, and his persona endeared him to many until his death in 1971 at age 69. At the museum, you can see several video segments of his many television shows and movie appearances during the later years of his life.

Our journey did not end with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and American Jazz Museum. In my next installment, I will recount our visits to Fort Osage and the Watkins Mill.

Never miss an installment in the adventures of Doug and Dan by becoming a $5-per-month donor to ThePerryNews.com. To get started, simply click the Paypal link below.

![Louis_Armstrong_(1955)[1]](https://theperrynews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Louis_Armstrong_19551.jpg)