In a surprising reversal of longstanding policy, the Dallas County Board of Supervisors not only voted in February to join the North Raccoon River Watershed Management Coalition, but Supervisor Mark Hanson got himself elected the first chairperson of the coalition at its July 12 meeting in Lake City.

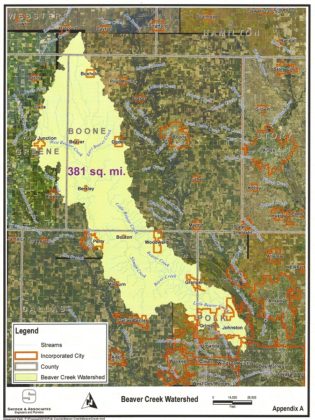

The supervisors’ change followed almost seven years of wariness about the financial entanglements and legal liabilities of the emerging regional groups, which are tasked with flood control and water-quality management at the watershed scale. That wariness led the board to reject in 2014 any involvement in the 13-member Walnut Creek Watershed Management Authority (WMA) and in the 25-member Beaver Creek WMA in 2016.

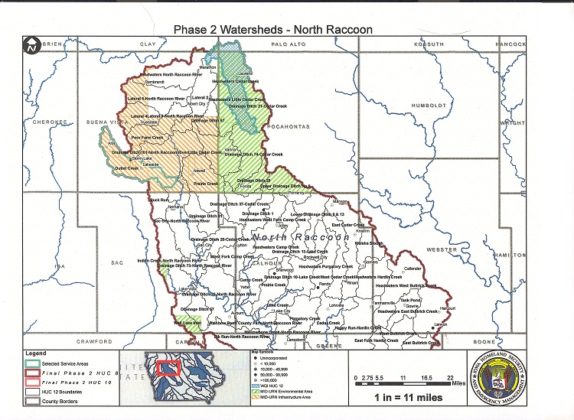

But with nearly 90 entities eligible to participate, the North Raccoon River WMA — it calls itself a coalition instead of an authority — proved too big and important even for the supervisors to ignore.

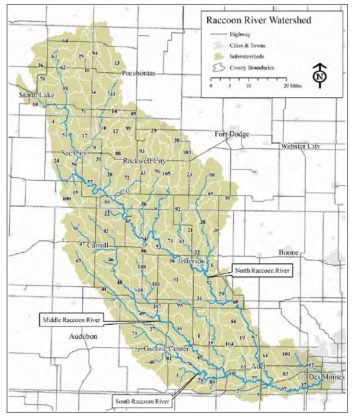

The North Raccoon River WMA is Iowa’s biggest in terms of its territorial extent. Fifteen counties are drained by the watershed: Boone, Buena Vista, Calhoun, Carroll, Clay, Dallas, Greene, Guthrie, Madison, Palo Alto, Pocahontas, Polk, Sac, Warren and Webster. Membership in the coalition is open to them plus to 14 Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCDs) and some 60 towns and cities.

The North Raccoon River watershed drains 2.3 million acres of cropland and provides drinking water to 500,000 people in Des Moines and the surrounding region.

The watershed is heavily tiled, with about 85 percent of the land in row crop production with a corn-soybean rotation. It is considered the most important and threatened waterfowl habitat in North America, supporting more than 300 migratory bird species.

Dallas County’s supervisors avoided joining all WMAs since the time they signed on to the Middle-South Raccoon River WMA in 2010. Now considered the state’s only failed WMA, the Middle-South Raccoon WMA has not met for several years.

“I guess the other reason we’ve stayed away a little bit,” Hanson said last year when the board rejected membership in the Beaver Creek WMA, “is we still are trustees for drainage districts, and there is the lawsuit stuff that is happening, if that makes a difference one way or the other.”

County supervisors across the state are breathing easier now on that score because one part of the Des Moines Water Works lawsuit was dismissed in January by the Iowa Supreme Court, and the rest was thrown out of federal district court in March. The five-member governing board of the Des Moines Water Works itself was very nearly dissolved by the Iowa Legislature in consequence.

In addition, an audible sigh of relief went up from agribusiness last October when the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals halted implementation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Clean Water Rule, called the Waters of the U.S. (WOTUS). The Trump administration and EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt have said they plan to withdraw the rule.

And as if for good measure, the Iowa Legislature last spring chastened even the mildest critics of industrial agriculture when it moved to zero out funding for the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University and the Iowa Flood Center at the University of Iowa.

The challenges posed by the WOTUS rule and the Water Works suit were decisively turned back. In other words, Big Ag is firmly in the saddle. From the American Farm Bureau Federation and the commodity front groups to the corporate giants like Tyson and JBS, Dow-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto, to the banks and insurance companies that underwrite them all — these are still the powers that be in Iowa agriculture.

In spite of industrial agriculture’s predominant position of strength and security, the Dallas County Board of Supervisors remained reluctant to join the WMAs. Hanson only managed to persuade his fellow board members to sign the North Raccoon River 28E agreement in February by promising that if they voted down his motion, he would immediately follow it up with a motion to withdraw from the Middle-South Raccoon River WMA, which the board played so large a part in forming.

Supervisor Kim Chapman said he opposes on principle any growth in government bureaucracy, and he sees the North Raccoon River WMA as an example of just such needless growth. Supervisor Brad Golightly said WMAs are actually the thin end of the wedge in the regulation of agriculture, a sneaky way for those he once called, in a different context, “obsessive activists” to forward their radical environmental agenda.

Golightly is probably correct. Most of the conservation practices pursued by the WMAs are well known in Iowa and have been used on a small scale for many years, and most of them serve the cause both of flood control and water quality at the same time.

The funded practices include cover crops, grassed waterways, grade stabilization structures, water and sediment control basins, nutrient management, tile line bioreactors, tile outlet terrace systems, prescribed grazing, residue and tillage management, pasture and grassland management, riparian buffers, wetland restoration, streambank protection and shoreline protection.

None of these practices is controversial, and all have been proven effective is keeping soil, water and fertilizer on the land and out of the rivers. The fear is that a regulatory regime might be put in place by the Washington bureaucrats, that nutrient loss from fields, for instance, might be monitored and treated as a point-source pollutant, that farmers might be obliged by law to have water-quality plans for their operations and that their eligibility for publicly subsidized crop insurance, for instance, might be made contingent on their meeting target goals for soil erosion and nutrient loss.

Farmers want to reduce erosion and nutrient loss. They also want to maximize yield. When these interests conflict, they want to be free to choose their own course of action just as they always have been. The fear is that a WMA is just a backdoor for the R-word: regulation.

A further cause holding back the supervisors from plunging into the newly forming WMAs was a once-bitten-twice-shy attitude left over from the fallout of the 2006 scandal that rocked the Iowa Workforce Development’s Central Iowa Employment and Training Consortium. Dallas County was left on the hook for about $40,000 at the end of that episode, Hanson said.

Yet the supervisors finally overcame these objections, and Hanson now chairs the North Raccoon WMA behemoth. He and Katie Rock, a Polk County SWCD commissioner who was elected treasurer of the North Raccoon coalition, attended the July 20 meeting of the Beaver Creek WMA at the Towncraft Center in Perry in order to make themselves known to that group.

The Iowa Legislature created the legal basis for WMAs after the disastrous 2008 floods as a way for multiple political jurisdictions to collaborate on solving flooding and water-quality challenges that none could solve alone.

There are 57 watersheds in Iowa, according to the U.S. EPA, and 18 have so far seen WMAs created to manage their waters. WMA membership is open to any county, city and SWCD within a watershed.

The purposes of the WMAs, which have no taxing authority or power of eminent domain, seem fairly straightforward. They were created in order to:

1. Assess the flood risks in the watershed.

2. Assess the water quality in the watershed.

3. Assess options for reducing flood risk and improving water quality in the watershed.

4. Monitor federal flood risk planning and activities.

5. Educate residents of the watershed area regarding water quality and flood risks.

6. Seek and allocate moneys made available to the WMA for purposes of water quality and flood mitigation.

These aims might sound benign, but the word authority in WMA can be a cause of concern.

“We joke about it being a watershed management authority,” said Mark Land of Snyder and Associates, who has been like a midwife in the formation of several WMAs around Iowa, “but it doesn’t really have any authority.”

The next meeting of the North Raccoon River Watershed Coalition is Sept. 20 at 10 a.m. at the Stewart Memorial Community Hospital, 1301 W. Main St. in Lake City.