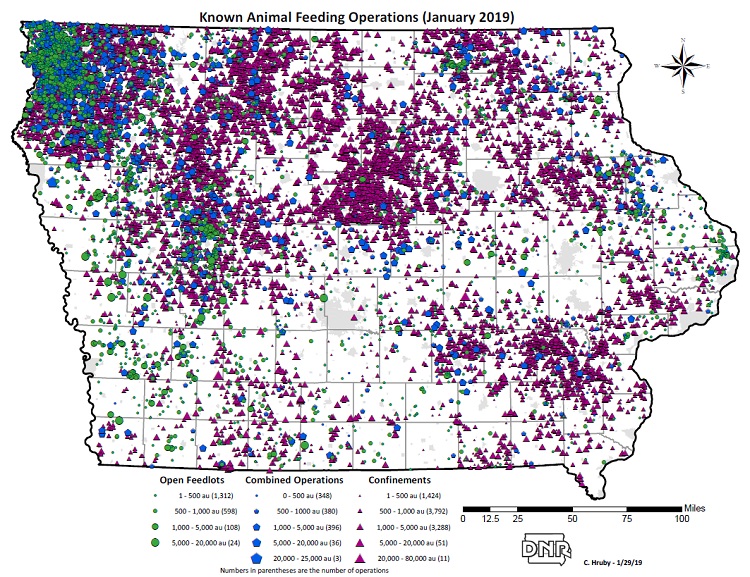

We are now seeing a corporate takeover of dairy production, which is the last bastion of full-time, independent family farms in animal agriculture. Poultry was the first to come under corporate control, the second was beef, then pork and now dairy.

We are now seeing a corporate takeover of dairy production, which is the last bastion of full-time, independent family farms in animal agriculture. Poultry was the first to come under corporate control, the second was beef, then pork and now dairy.

The corporatization of each sector has been a bit different, but all have followed the same basic pattern or process. We can now see that pattern unfolding in dairy production.

I am more familiar with the corporate takeover of the pork industry than for poultry or beef. It happened during the 1990s, while I was still an active faculty member of the University of Missouri. The corporate challenge was to displace independent hog farmers, many of whom were very efficient producers.

During the 1990s, the University of Missouri operated a mail-in records program for Missouri farmers. Producers would mail in copies of their purchases and sales records, which the university would use to prepare financial statements that included their costs of production and profits.

Each participant would be provided with a summary of financial results for similar producers so they could compare their performance with others — benchmarking. We had enough records for farmers who specialized in hog production to provide them with average production costs for the most efficient and least efficient as well as the average hog producers in the program.

We also had accurate information regarding costs of production in the large corporate-affiliated feeding operations that were trying to gain a foothold in the state at the time.

The mail-in records indicated the large corporate feeding operations likely would be more efficient than the least efficient one-third to one-half of existing Missouri hog producers. However, the corporate operations were likely to be less efficient than the most efficient one-third to one-half of existing hog producers.

In other words, any cost-of-production advantage for the large corporate operations would be small in comparison with the average existing Missouri producer. However, by being vertically integrated into pork processing and distribution as well as hog production, the large corporate operations were ultimately able to drive even the most efficient independent hog producers out of business.

The key to the corporate takeover was that they could easily outlast the least efficient one-third of independent producers during the inevitable depression in hog prices resulting from their expansion in production.

But the corporate operations didn’t even need to be more efficient than the average independent producer. The corporations were involved in pork processing as well as production.

The packers lowered wholesale pork prices enough to allow the pork from hogs under their control to clear the market, but only enough to leave prices seriously depressed in markets where independent producers were forced to sell. Any corporate losses on their owned or contract hogs were largely offset by wider margins of profit for hogs purchased from independent producers.

Independent producers not only were forced to sell at large losses, but some couldn’t find markets at any price. During the late 1990s, market prices for hogs dropped to a low of $8 per hundredweight (cwt.) while average costs of production were more than $40 per cwt.

Enough independent producers were eventually forced out of business to allow hog prices to return to more reasonable levels. However, as the less efficient producers were forced out of business or became corporate contract producers in order to survive, a larger portion of total hog production came under corporate control.

Eventually, even the most efficient independent producers couldn’t survive these market conditions. Even the vertically integrated corporations lost money at times during the takeover, and some were forced out of business as they competed for market share and control. The surviving corporations succeeded in taking over virtually complete control of the hog industry — from hog genetics to finished pork products.

Unfortunately, this is the harsh reality now confronting smaller independent dairy producers. The unbridled expansion of large confinement dairy operations have increased total production and depressed milk prices to unprofitable levels for most independent producers. Weaker consumer demand for dairy products has magnified the depression.

The least efficient independent producers have already been forced out of business by the previous expansion of large corporate operations. The remaining independent producers, including organic producers, are now at risk.

The government has long been involved in the pricing of milk, which makes the milk market somewhat different than for other animal products. In addition, cooperatives are among the largest corporate processors of milk but, unfortunately, are acting more like corporations than cooperatives.

It remains to be seen whether the large corporate dairy operations have gained sufficient market power to drive out the most efficient independent dairy producers. Regardless, the remaining independent dairy farmers can’t afford to ignore the lessons learned from the corporatization of poultry, beef and pork.

For a fuller explanation of the takeover process, visit my website.

John E. Ikerd, professor emeritus of agricultural economics at the University of Missouri, writes and speaks on issues related to sustainability with an emphasis on economics and agriculture.