There was a time when Dallas County was one of the most important coal-mining counties in Iowa. While this way of life vanished decades ago, the memories live on, from the Hotel Pattee in Perry to the Waukee Public Library to the many descendants of mining families who still live in the area.

From Moran to Woodward to Waukee, Dallas County thrived with the increased demand a century ago for coal to power train locomotives and heat businesses and homes. Coal was a relatively cheap, plentiful energy source. With ample supplies of coal, Dallas County became a land of opportunity for immigrant miners from Europe and beyond.

Coal mining started in the Van Meter area as early as the 1870s. By the early 1900s, coal was discovered in Des Moines Township east of Woodward, leading to the creation of the Scandia and Phildia mining settlements. After the Phildia mine was abandoned in 1915 and the Scandia mine closed in 1921, miners moved on to the Moran mine, which opened in 1917 west of Woodward.

Moran is not on most maps today, but there was a time when Moran was a bit of a boom town. The Angus and Moran Room at the Hotel Pattee in Perry recalls the history of Moran and Angus, once-thriving mining towns to the east and northwest of Perry that once boasted thousands but now have at most a handful of residents.

Living with danger

On the opposite side of Dallas County, coal mining also transformed the Waukee area in the early twentieth century. The Harris Mine opened Sept. 20, 1920, just two and a half miles northeast of Hickman Road in Waukee.

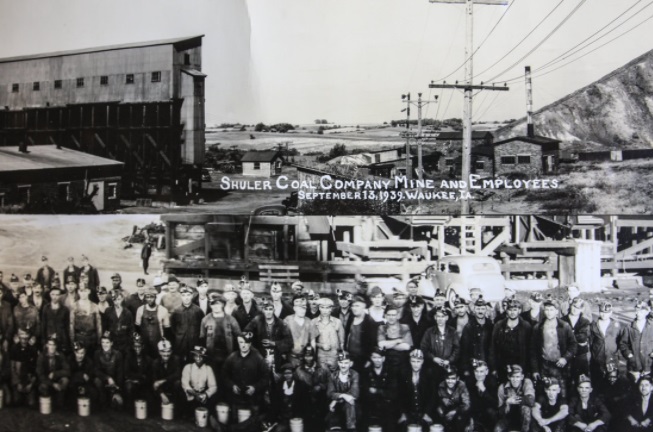

By 1921 the Shuler Coal Company of Davenport opened a coal mine on Alice’s Road, one mile east of the Harris Mine. At its peak production, the mine employed more than 450 men.

The Shuler Mine became one of the largest producers of coal in Iowa, and it had one of the deepest mine shafts — 387 feet deep. The mine produced coal for Iowa State University as well as for local railroads, businesses and homes.

The miners worked in the Shuler mine with the help of more than 30 mules, bringing up hundreds of tons of coal a day and millions of tons of coal over the mine’s 28 years of operation. The miners’ work day often started at 6 a.m., and they wouldn’t return home until 4 p.m. or later.

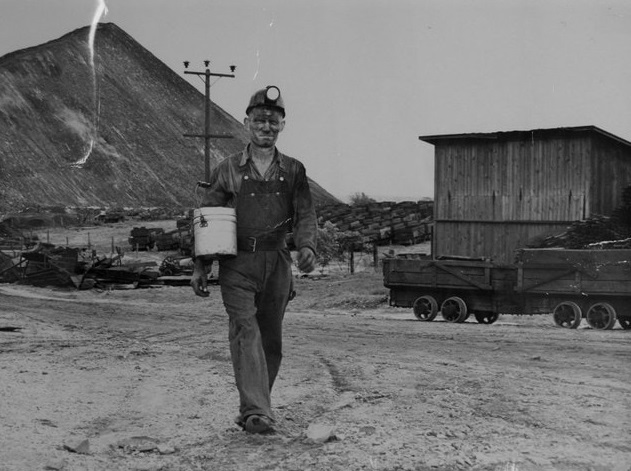

Mining was dangerous, dirty work. Miners used dynamite as well as heavy picks to break coal loose from the coal veins. When the siren blew, it was a sign that a miner was in trouble, or there had been a cave-in.

“I can remember the whistle blowing in succession to let people know there had been an accident,” said Angelo Stefani, whose uncle was killed in a mining accident. “I can also vividly member women coming out of their homes to see what happened. They were hysterical.”

Life in Waukee’s coal mining community

The Shuler mining camp was home to Italians, Croatians and people of other ethnicities. Most families lived in small, simple houses with no running water, but they often raised chickens and tended enormous gardens where they grew a variety of vegetables.

Work wasn’t always steady. Dallas County’s coal mines often closed in the summer, when demand for coal dropped off in the warmer months. Miners would often work for local farmers or do odd jobs around the community to help pay the bills.

Some of the miners’ wives, especially those in Italian families, worked at local restaurants, such as Rosie’s and Alice’s Spaghettiland near Waukee, in order to supplement the family’s income.

Source: Waukee Area Historical Society

Alice Nizzi (1905–1997) opened Alice’s Spaghettiland in the Shuler mining community just north of Hickman Road in 1947. The restaurant’s waitresses were required to wear white, starched uniforms. Alice’s became a destination and Waukee-area institution for decades until it closed in 2004.

The Waukee Area Historical Society hosted a fundraising dinner in the spring of 2014, featuring Alice’s spaghetti and Italian salad. Hundreds of people now attend this fun event, which has been held each April for the past few years.

Remembering the grape trains

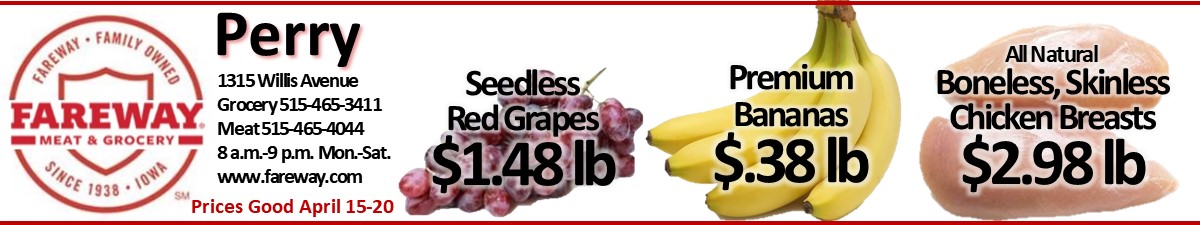

For Italian families in the Shuler mining camp, one of the highlights of the year was the arrival of the annual trainload of grapes for making homemade wine.

“Excitement spread throughout the camp when the train arrived, and most of the people from the mining camp came to help unload the box cars,” said Gilbert Andreini, whose memories are recorded at the coal mining museum at the Waukee Public Library. “It was like a celebration.”

By the time the Shuler mine closed in 1949, Iowans began looking to energy sources other than coal for home use, such as electricity, natural gas and heating oil. In addition, the railroads were converting from steam to diesel engines, reducing the need of coal for locomotives.

While Dallas County’s coal mines have vanished into history, those who grew up in the mining camps will never forget how these areas grew into close-knit communities. Everyone knew everyone else and helped each other out, recalled Bruno Andreini.

“I’m very proud of those times,” Andreini said. “Anyone from that community is like a brother or sister to me. Even though we were poor, we had things that were far more valuable than money.”

Iowa author Darcy Maulsby will be speaking at Hotel Pattee Sept. 11 from 7–9 p.m. as part of Hometown Heritage’s fall programming series. For more information, visit the Hometown Heritage website. You can also learn more about Darcy on her website, and her book is available for pre-order on Amazon.