“The Birth of a Nation” was released Feb. 8, 1915. In the course of three hours, D. W. Griffith’s controversial epic film about the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction depicted the Ku Klux Klan as the valiant saviors of a post-war south.

The film was an instant blockbuster. “The Birth of a Nation” rekindled the KKK in America.

The states ratified the 18th Amendment Jan. 16, 1919, and it took effect in 1920, prohibiting “intoxicating liquors” in the U.S. During the next decade, the criminal justice system expanded as police disproportionately arrested people who were immigrants, black, poor and working class.

But there were also plenty of Prohibition-supporting white Protestants who thought the law wasn’t doing enough to stop the bootleggers they read about in the tabloids. That’s where the revived KKK stepped in, gaining prominence through the 1920s as the self-appointed defenders of American values.

The Klan sold itself to those white people as a law-enforcement organization that could do what the government couldn’t and put a stop to the Catholic immigrants supposedly violating the law. The Klan of the 1920s was unusual in that its primary focus was on Catholics and eastern and southern European immigrants.

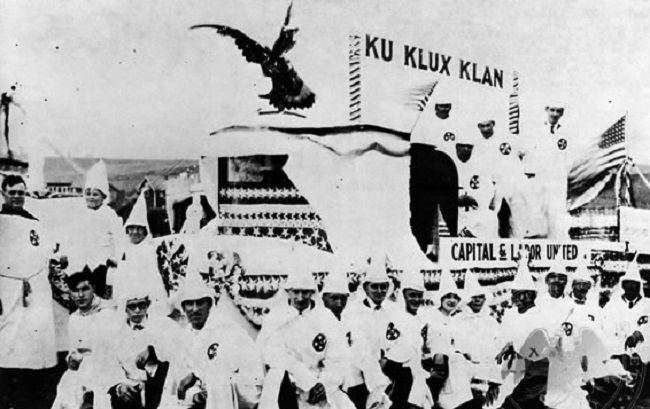

Rather than the violent, racist extremists of popular lore and current observation, Klansmen of the 1920s appeared as more mainstream figures. Sharing a restrictive American identity with most native-born white Protestants after World War I, hooded knights pursued fraternal fellowship, community activism and local reforms, and they paid close attention to public education and law enforcement, especially Prohibition.

In an oat field two miles east of Perry, the local branch of the Ku Klux Klan had a meeting July 31, 1923, complete with a fiery cross, visible to passing cars on old Highway 17. Hooded sentinels, some on garbed horses, guarded the field. The Rev. Tom Roberts of Des Moines delivered a godly lecture.

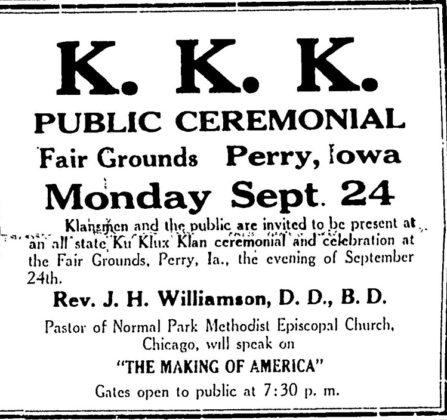

Two months later, on Sept. 24, 1923, some 6,000 people packed into the fairgrounds for a semi-public meeting of the Klan. About 2,000 Klansmen and Klanswomen were present, starting the celebrations with a parade around the half-mile track. After the parade, the Rev. J. H. Williamson gave an address entitled, “The Making of America.”

A large number of Perry’s white folks were also attracted to a Klan meeting on the old Perry-Ogden road, just north of the old People’s Church in April 1924. A huge, lighted cross was hung from the windmill, and two young people from Boone were married. A parade of robed Klansmen followed the breeding pair to their nuptial couch in a show of race power.

The largest Klan ceremony in Iowa came to Perry in June 1924. Estimates show at least 15,000 were here to watch the parade and attend the ceremonies. More than 5,000 Klansmen and Klanswomen attended the ceremonial activities at the fairgrounds. The address of the day was entitled, “Making America Great Again.”

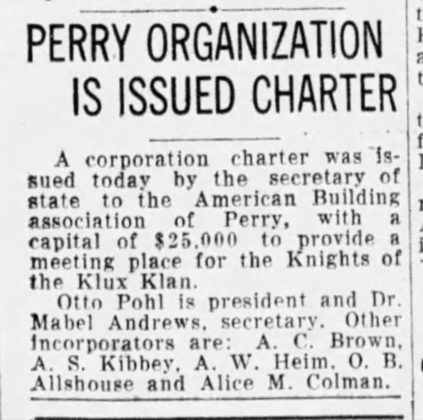

With the Klan organization working at every precinct in Perry, in June 1923 they made a clean sweep, with Klansmen and Klanswomen to represent the city of Perry. That night they burned two fiery crosses, each eight feet tall with five-foot arms, one on the Washington High School grounds, where the U.S. Post Office now stands, and one on Milwaukee & St. Louis Railroad property on Second Street.

One of the largest funerals ever held in Perry was Jan. 22, 1925, for Walter Schell, a prominent farmer and Klansman who died at King’s Daughters Hospital. More than 200 Klan and some 1,500 people from Perry came to services at the Christian Church.

A huge cross was formed over his grave by the 200 Klansmen and Klanswomen in attendance, and Klan officials took charge of the last rites. All the Klan filed past the casket before it was lowered into the grave.

Cold, wet weather did not stop the Klan from staging a parade in Perry Oct. 8, 1925. There were two bands, two drum corps, two floats and about 200 robed Klansmen and Klanwomen. The bands and drum corp wore special uniforms, and the parade was enlivened by a line of red torches.

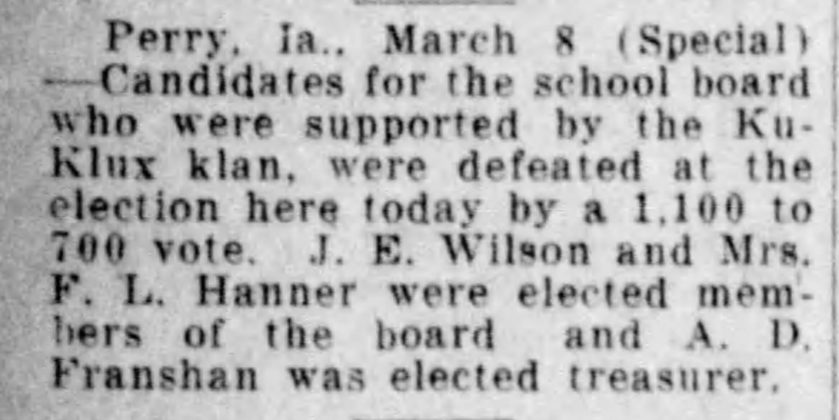

The Klan’s peak year was in 1924, when they influenced many elections across the country, including an Iowa race for the U.S. Senate. The Klan helped the campaigns of many school board members, succeeding in electing representatives sharing their point of view, but in 1926 many of them were voted out.

On Oct. 29, 1929, Black Tuesday hit Wall Street as investors traded some 16 million shares on the New York Stock Exchange in a single day. Billions of dollars were lost, and thousands of investors were wiped out. By July 1932 the stock market had lost 89 percent of its value.

In the aftermath of Black Tuesday, America and the rest of the industrialized world spiraled downward into the Great Depression, the 10-year economic disaster that was the deepest and longest-lasting economic downturn in U.S. history.

At the beginning of the 1930s, more than 15 million Americans, fully one-quarter of all wage-earning workers, were unemployed. By 1932 many Americans were fed up with Herbert Hoover and the Klan and what Franklin Delano Roosevelt later called the “hear-nothing, see-nothing, do-nothing Government.”

The Klan’s program for making America great again was not working.

Yet the Klan persisted in Perry. The group owned land west of the old fairgrounds, where their “cabin” was located. The Klan also had second-floor offices in downtown Perry for many years and in 1936 installed a fiery-cross sign in front of the building. The cross was about six feet tall, painted white and covered with red light bulbs.

In the Perry paper’s society column on “Clubs and Lodges” in the 1940s, one can read about Klan potlucks, luncheons and plate suppers at the Legion and at the “cabin.” Klan store owners in the 1940s had small signs in their stores so that members knew where to shop.

By the 1950s and the rise of the civil rights movement in the U.S., most of Perry’s overt Klan regalia was relegated to back closets and cedar chests, and the Klan’s local history was thereafter discreetly omitted from the town’s more flattering self-portraits.