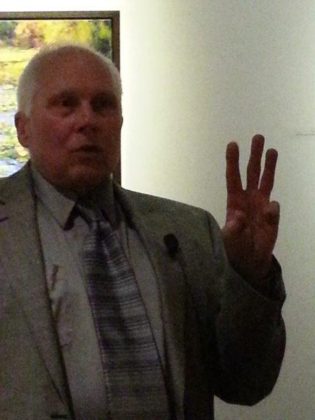

“You’re asking me if I miss my children?” said landscape painter Gary Bowling.

“No.”

Bowling was answering an audience question about selling his paintings — his “children.” By the time I’ve finished a painting, he said, “I’ve nailed it down. I’ve found it.” The paintings then become “food for the next three paintings.”

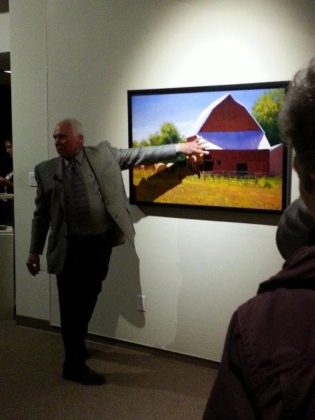

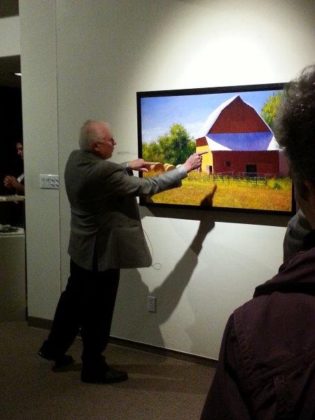

Painting is a “problem-resolution” process for Bowling, who spoke last month at the Brunnier Art Museum in Ames. It could be orange as a color problem that leads to painting orange cones and orange construction barriers, which in turn leads to further painting of landscapes and an exploration not only of orange but also of barricades and shadows and how they work and how highways give one clues as to how we are isolated from something else.

Bowling said he is interested in things many of us overlook but that “populate our way of thinking about places”—stop signs, shadows, jet trails. From his perspective, these are things that are dividing and defining our landscapes—“things that divide our field of view.”

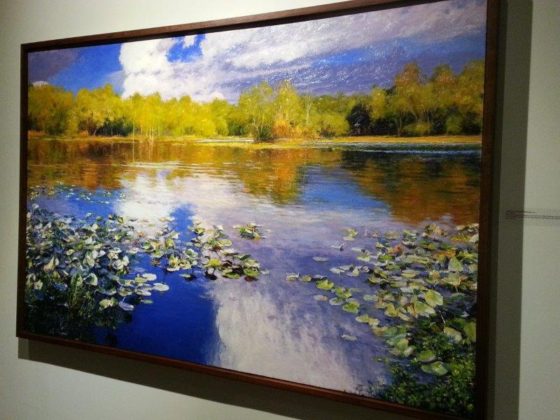

He’s enamored with the kinds of ways a sky can be divided up and also by what goes on outside the frame—shadows that encroach upon the image and indicate something more is going on outside the frame.

“How do you describe something?” Bowling said. “I have to be a poet and attempt to convey some essence of my experience. How can I get somebody else to understand a little bit of what I experienced?”

He said art should “carry you someplace you haven’t been before. It should speak to you across time and across space.” But how does “the structure of a painting do that?” Bowling asked. “It’s kind of magical.”

After viewing good art, you should not be the same person, according to Bowling.

“You grow a little bit.”

Likewise, the art itself will grow and “will have a new significance” with each successive viewing, he said, noting he is continually struck by “that beautiful place that sort of defies verbal description” and gives him a sense that “something is there.”

He said he photographs such places and then collects subject matter reference points, such as computer images, that relate to the idea. He synthesize them, and eventually a painting emerges.

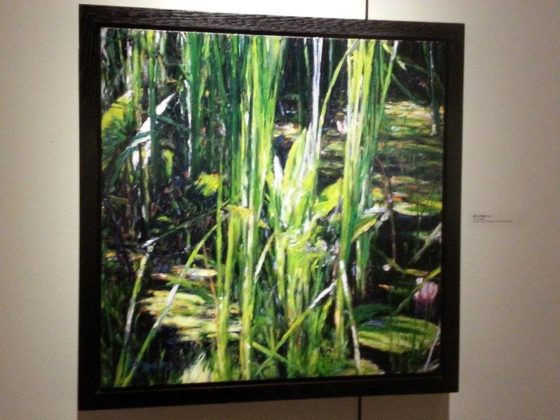

In his paintings, Bowling attempts to take an experience that haunts him, something “mesmerizing” that most people find ordinary. He tries to make it the “story of you with that place, nobody else to capture your attention—at one with it.” It can be a “childlike thing of crawling around in the environment—trying to find a way to escape into nature,” he said, or a quest to “find some kind of common ground, create touchstones.

Throughout the creative process, he asks himself, “Is this making me feel that thing?” He tries to “crystallize and freeze something that’s too elusive to hang on to. It’s an inventive process. I probably know how to do it, but I don’t know how to describe how I do it.”

In seeing his work, the audience was already convinced that he definitely “knows how to do it.”

When asked why his landscapes are rarely winter scenes, the knowing Iowans understood when he responded that winter has never been a place Bowling wanted to escape to.

“Why landscapes?” someone asked.

Bowling said his office at Westmar College in LeMars, Iowa, was in the basement where he never really saw the sun—no windows. Then driving across Iowa one day and experiencing the view and the sunshine, he thought, “This is fantastic. It’s kind of nice to not be in the basement.”

So that windowless office assignment may have done more to make him a landscape painter than almost anything, he said. I wonder whether the person responsible for office assignments all those decades ago realizes the contribution s/he has made to the art world.

University Museums has brought together many of Bowling’s works, along with several loaned works, in a gorgeous exhibition at the Brunnier Art Museum in Ames through July 31.

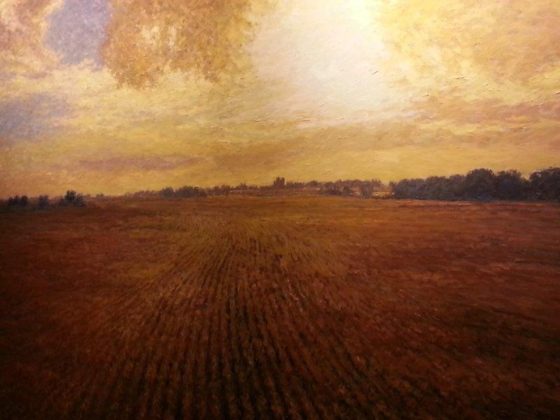

In the meantime, if you wander into the Hotel Pattee, you can experience Bowling’s large landscape on the third-floor landing. When specifically asked about this painting during his lecture, he did recall this art piece and spoke about how the “horizon divided the field, suggesting that it makes a separate universe, but the worlds belong together—they need each other.”

That’s true of the art and non-art pursuits in our world, our American landscapes, and our diverse American citizenry—our worlds belong together, they need each other, and art can help accomplish this.