Thanks to an accident of history, Perry’s residential neighborhoods have never been sharply separated by race or class. Visitors might sometimes criticize Perry’s housing as an uneven patchwork, with large, fine houses found standing side by side with much more modest dwellings, but this diversity in housing has also fostered a racial and socioeconomic diversity in occupants.

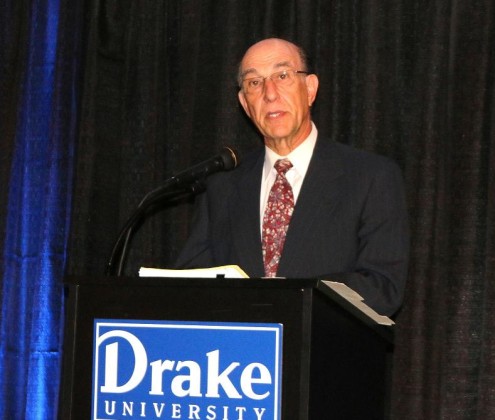

This point about Perry’s housing patterns was made at Drake University last week by Mayor Jay Pattee when he introduced Richard Rothstein, an historian and research associate with the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. Rothstein was in Des Moines to deliver the 2015 Sussman Lecture, an event of the Harkin Institute for Public Policy and Citizen Engagement.

In his introduction, Pattee told the audience of 200 in the Sussman Theater in Drake’s Olmstead Center about Perry’s humble beginnings, its growth with the railroads and the curious story of houses moved to Perry from Angus, a mining town lying north of Perry and once containing nearly 8,000 residents.

“That town dried up with the mines,” Pattee said, “and people literally dragged houses to surrounding farmland and into the city of Perry, and those houses became some of the first homes in Perry.”

The Angus homes were soon joined by other dwellings built as people moved to Perry, both those the railroad brought and those who found their way west and ended up settling in Perry, Pattee said.

“As you looked at how the homes went up,” he said, “it was a small home next to a large Victorian next to one that was dragged from Angus. The town seemed to develop that way. There was no exclusive neighborhood.” There was no poor side of town or line of shacks across the tracks.

Pattee also outlined the railroad’s withdrawal from Perry in the late 1970s and Oscar Mayer’s sale of the meatpacking plant west of Perry to IBP in the late 1980s. It was IBP’s policy to pay lower wages and chiefly to employ Latino laborers, many of whom stayed and raised families in Perry. The most recent U.S. Census shows Perry’s population is now 31 percent Hispanic, and the town is often seen as a model of successful racial integration in Iowa, Pattee said.

“I ask myself,” said the two-term mayor, “How can we claim credit for the fact that people came into Perry so easily? and the answer is that when the railroad pulled out and when the first meatpacking plant closed, it left vacancies in housing all over the city of Perry. Some were rentals, and some were owned homes, but I always tell people who come to our town, no matter what ethnic group they belong to or what level of society they are in terms of middle class or lower class, there’s a good chance they’ll be my neighbor.”

While Perry cannot take moral credit for an accident of history, we can still be thankful for what did not happen, Pattee said.

“What happened in Perry and why we’ve been so successful, I believe, is not anything that we did, but it’s what we didn’t do,” he said.

What many towns and cities in the U.S. did do, starting early in the 20th century but increasingly systematically after World War II, was the subject of one of Rothstein’s recent articles for the Economic Policy Institute, “From Ferguson to Baltimore: The Fruits of Government-Sponsored Segregation.”

What many towns and cities in the U.S. did do, starting early in the 20th century but increasingly systematically after World War II, was the subject of one of Rothstein’s recent articles for the Economic Policy Institute, “From Ferguson to Baltimore: The Fruits of Government-Sponsored Segregation.”

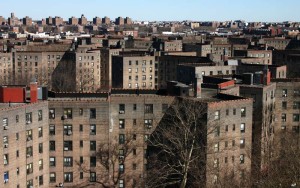

In his Drake lecture, Rothstein demonstrated in great detail and with abundant evidence the effects of federal, state and local housing laws that excluded African Americans from home ownership and essentially created the urban ghettos still seen in many U.S. cities.

He also explained why most Americans today are ignorant of these historical roots of poverty. Rothstein described what he called a “national myth of de facto segregation,” which teaches ghettos somehow sprang up of themselves through, in the 1974 words of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, “unknown and perhaps unknowable factors, such as immigration, birth rates, economic changes or cumulative acts of private racial fears.”

According to Rothstein, however, the “factors that created racial ghettos in the major metropolitan areas of this country today are not unknown and unknowable. They are quite easily knowable and they once were well known, but we as a country have managed to forget them. If I can use an infelicitous word, we’ve whitewashed our memories about how segregation took place.”

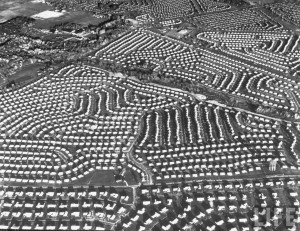

Rothstein described a number of public-housing “policies, practices and prejudices” permitting housing projects to be segregated by design, from the white-only and black-only government-built projects that sometimes replaced previously racially integrated neighborhoods, to the mid-1950s’ programs that offered federally guaranteed construction loans for developers building large suburban housing subdivisions but only on the explicit condition that the homes not be sold to African Americans.

Among the most harmful housing laws, according to Rothstein, was the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) exclusion of African Americans from the low-interest, federally insured home loans it extended to white people.

He used the Long Island, New York, community of Levittown as one example. The sprawling Levittown subdivision opened in 1947, and houses sold for $7,000 to $8,000 each. In today’s dollars, that is about $100,000 to $120,000 homes, Rothstein said.

“Today those homes sell for $400,000, $500,000, $600,000,” he said. “Those white families who were permitted — subsidized — by the federal government to purchase those homes, over the next three generations they gained some $500,000 in equity appreciation. Some of it was cashed in to send their children to college. Some of it was used to finance their retirement so that their children didn’t have to support their parents in their old age.”

African Americans who “were identical in every respect except for their race” but were excluded from FHA-guaranteed mortgages and barred from buying homes rented apartments instead and “gained none of that equity appreciation,” Rothstein said.

“As a result, today — and this happened all over the country. This is not a Levittown-exclusive experience. I’ve described the St. Louis suburbs and the San Francisco suburbs. There’s no major city in the country where you can’t find these developments — as a result, today African American family incomes are on average about 60 percent of white family incomes. African American wealth — wealth is primarily in this country the result of home equity — African American wealth is 5 percent of white wealth. So you have income with a ratio of 60 percent and wealth with a ratio of 5 percent, and that difference is almost entirely attributable to explicit federal sergregationist racial policy. It’s not the accident of people having poorer educations. It’s not the accident of people not knowing how to save. It’s not the accident of not wanting their children to go to college. It’s the result of explicit federal racial policy that we have forgotten.”

Rothstein described similar policies on the local level, such as restrictive covenants attached to property deeds in many white neighborhoods prohibiting the sale of properties to African Americans. County tax assessors across the country also systematically over-assessed the value of homes owned by African Americans and under-assessed the value of homes owned by whites, with the result that African American homeowners paid higher taxes, leaving them less money for upkeep and maintenance and helping to create ghettos.

Since African Americans were excluded from government-insured FHA mortgages, Rothstein said, the only way many could buy a home at all was on the contract system, also known as the installment plan. Buying a home on contract builds no equity for the buyer, and if he misses one payment, he loses his entire investment. The pressure never to miss a payment led many African American homeowners to subdivide their houses and to neglect maintenance. This led to the stereotypical traits of ghettos: over-crowded and impoverished people living in run-down neighborhoods.

“The consequence of that,” Rothstein said, “is that when middle-class African Americans tried to bust out of the ghetto and buy homes in adjoining white neighborhoods, white families concluded that they were slum dwellers and they were going to bring slum characteristics with them, not understanding that the slum characteristics were not characteristics of the families but were characteristics of the public policies that had created those economic conditions. White flight resulted. It’s true that part of the segregation explanation is white flight, but the white flight can’t be separated from the public policy conditions that created slum conditions in African American neighborhoods and made whites fear that if their neighborhood was inhabited by African Americans, their property values would decline.”

All of these laws and policies of racial separation were once well known, Rothstein said, but a kind of national amnesia has led us to forget them.

“If people understand the history, if they understand the extent to which our segregated metropolitan landscape was created by us, by our country, that the citizens are responsible for it, then we will understand or at least begin to understand that we have an obligation to reverse it,” Rothstein said. “My final charge to you is to become familiar with this history yourself, make sure that others become familiar with it, so that we can begin to create the political possibility in this country for remedying what is perhaps the most serious crime in our nation’s history.”