He was one of the smaller, younger members of our gang in the northeast neighborhood of Perry, when we were of an age that chasing bandits and cattle rustlers, playing cowboys and bad guys was our only reason for being.

A good looking, affable kid, always smiling or laughing, fooling around.

A decade later, he intervened for me, saving my ass from an angry mob.

The Center Street area of Des Moines, the epicenter of protests and riots during the late ’60s, was where I found myself, inadvertently, one fine afternoon in the spring of 1969 after a job interview at the Colonial Penn Life Insurance Co. on Grand Avenue.

Of course, I was decked out in my best rioting-and-pillaging outfit for the occasion: a navy blue suit (I had only one), brand new, black wingtip broughams, a Van Heusen white dress shirt (I possessed two) and a wide, red tie.

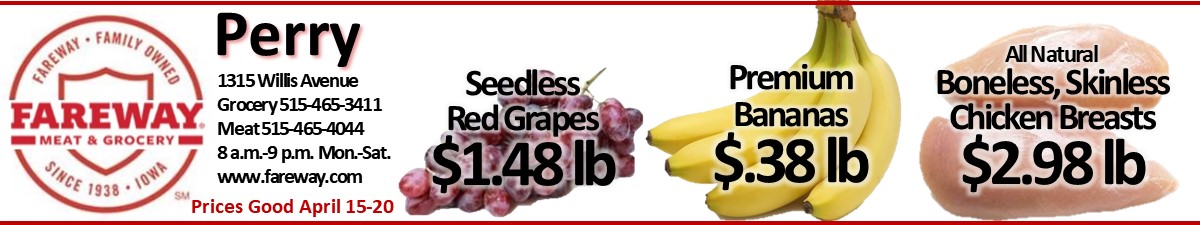

I was driving our 1969 gold Monte Carlo with black vinyl top, showing only 300 miles or so on the clock since January, when I purchased it off the showroom floor from Lauterbach Chevrolet with a loan from the Perry State Bank.

I was hopelessly lost. The receptionist at Colonial Penn had recommended a good cafe north of their offices a few blocks, where I could get a decent hot beef sandwich and a piece of pie for my kind of price.

So after a very late lunch, I had no more job interviews that day, and I tried to find my way out of Des Moines to head home to Perry on Highway 141.

I ended up stopped by the lights at the intersection of Center Street and something else in the middle of a construction zone mess for the new freeway.

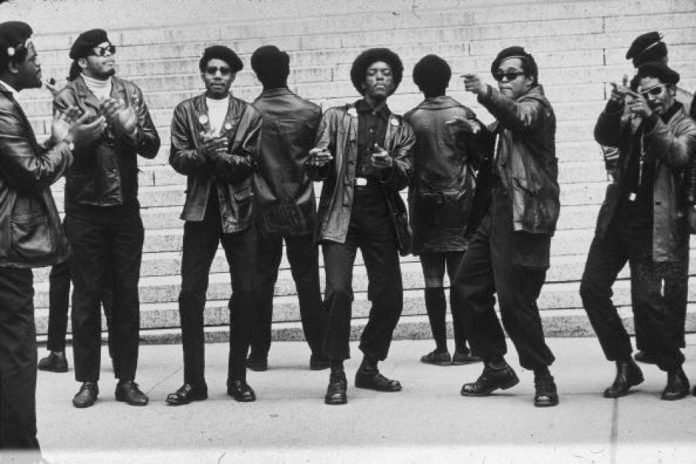

Before I knew it, 50 or more black youths had surrounded my car, climbing on top of it, pounding with their fists and screaming at me.

Then a smiling face looked in.

It was Orrie Ewing, my boyhood pal from Perry, all grown up.

He waved and motioned for me to roll down the window after he had told the others to stop beating on my car. He held great sway over this bunch. They did it like Orrie had flipped off their anger switches.

I could not have been more stunned if he had parted the Des Moines River, picked up my car with me in it and flew us home.

I pushed the button lowering the window (the first car I had ever owned with such a highly-suspect feature).

“Bill Reiter, my man! What in the hell are you doing in Des Moines? And here on Center Street for Jesus’s pity sake?”

“Just came down for a job interview.”

“You outa the army then? Last I heard, you were slipping and slopping around rice paddies over there.”

One of the other guys said, “Who the fuck is that, man?”

“Shut up, fool! This is my friend from Perry, and that’s all you got to know,” Orrie said, no longer smiling. “Bill, I’m sorry about that. So, you outa the army, you were saying?”

“Yeah, thank God, I am.”

“Oh, man, I just heard about your mom’s accident. I’m really sorry, Bill. She was a gracious, cool lady! A great mom.”

“Thanks, Orrie. Yes she was.” There was an awkward pause. “So what are you doing with yourself these days?”

“Not much. Just hanging out, marching, protests and shit . . .”

“How’s that going?”

“Well, don’t believe everything you see on the news.”

“No, I never do.”

“Well, man, Bill, you better keep on going on. We need to catch up though, sometime . . . you and me. I’ll look you up the next time I’m back in Perry, okay? Now take care.”

“That’d be great Orrie. You take care.”

I drove on home and, sadly, never saw or heard from Orrie again.

Great story, Bill! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for sharing that precious memory. Well told, Bill.