We shall never achieve harmony with land, any more than we shall achieve absolute justice or liberty for people. In these higher aspirations, the important thing is not to achieve but to strive.

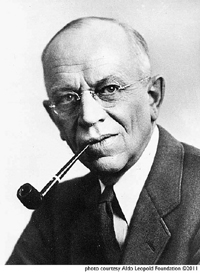

–Aldo Leopold

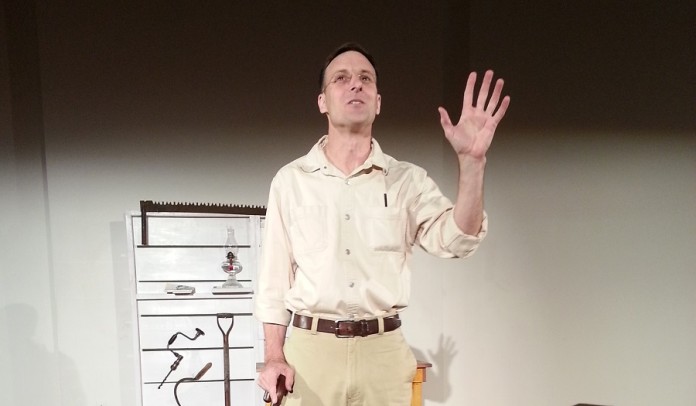

The woman next to me cried when Jim Pfitzer, playing the role of world-renowned naturalist and Iowa native Aldo Leopold, told of shooting a wolf and watching it die. Pfitzer, a nature lover himself, also got emotional and teary eyed during the question session afterward, when he recalled that Leopold never experienced the thousands of cranes that now abound at the Leopold Center in Wisconsin.

Who would have thought a one-act play about a conservationist, nature writer and outdoor enthusiast would bring forth such emotions?

Pfitzer performed “A Standard of Change,” the one-man, one-act play he wrote, at the Iowa State University Alumni Center in Ames April 9. The play recreates the experiences and anxieties that led to the essays in Leopold’s (1887-1948) most famous book, “A Sand County Almanac” (1949).

The play is set at the Shack, Leopold’s home in southern Wisconsin. Leopold’s writings from the Shack were deep reflections on the effects of human progress on nature’s wilderness. His philosophy of nature has had a huge influence on the modern environmental movement and is seen in practical ways in the work at the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at ISU.

When sharing a story about cranes, Pfitzer’s Leopold explains he’s not just hearing the cranes but feeling them in his chest. Similarly, the audience didn’t just hear Pfitzer’s words but felt them in their chests.

Many in the audience had read “A Sand County Almanac,” a classic in the field of conservation. I purchased a copy before I left and am anxious to read it and yet a bit leery.

It seems that many who read it once read it over and over again, sometimes annually, or so often—as with Pfitzer—that they’ve lost count. Many profess to learning more each time they read it. I love a great book, but I’m not sure I’m ready to commit to a lifetime of reading it—but it may grab me like it’s grabbed so many others in America and across the world.

Pfitzer describes himself as someone who would rather watch birds than TV and sooner canoe than drive.

He was eager to interact with the crowd and while happy that so many in the audience had read Leopold’s seminal book, he was even more thrilled that so many in the crowd didn’t know a thing about Leopold, and he was able to share Leopold’s story. He likes not only to share Leopold’s story but also to humanize him and pull him a bit off his pedestal and show him as one of us—someone with “blood on his hands.”

Bringing Leopold back to life 64 years after his death, Pfitzer shows him as someone who didn’t always do right by nature. He gives us a Leopold who once thought predators should be killed on sight but later changed his thinking about upsetting nature’s balance—upsetting the ecosystem of the mountain—a Leopold who evolved to “think like the mountain,” Pfitzer said

In the question period, we learned that Estella Leopold, the writer’s youngest daughter, whom he always referred to as “Baby,” selected the hat Pfitzer wears while performing his one-act play. Leopold also smoked a pipe, and Pfitzer uses a Hollywood non-tobacco version in his performance.

One audience member was concerned that he might light himself on fire one of these days when he puts his pipe back into his pocket, but he assured her it hadn’t happened and described the steps he takes to avoid it. He then noted that women always seem to ask him that question, but men don’t seem concerned about him lighting himself on fire.

Pfitzer is from Georgia and answers questions in a soft southern accent but squelching his southern roots while embodying Leopold. He’s happy he doesn’t have to mimic the voice of Leopold because no recording of his voice exists.

As a result of both his performance and his genuineness during the audience interaction, Pfitzer won the crowd over early and kept them on his side. Even so, he topped it off by saying that Midwesterners—Iowans included—are much nicer than the residents of the south with their reputation of southern hospitality.

While only 60 minutes long, the performance was as thought provoking as I’m sure Leopold’s book will be. Since he was born in Burlington, Iowa, and since we have the benefit of the nearby Leopold Center in Ames, I hope Leopold’s nature-centered philosophy will continue to spread across Iowa and the world.

As Leopold wisely said in “A Sand County Almanac,” “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”