Sen. Chuck Grassley, Iowa’s senior senator, dropped in Thursday evening on a meeting of the Woodward Lions Club. The visit was one step in his annual 99-county Iowa town hall tour.

Now in his 35th year as a U.S. senator, Grassley, 82, looked svelte in a gray suit and charcoal sweater vest. He spent an hour answering questions from about a dozen voters who attended the meeting, which was chaired by Woodward Lions Club President Paul Thompson, with Secretary Dale Schoening assisting.

Grassley was accompanied by Alec Kennedy, his regional director from the Des Moines office. Kennedy said the Woodward meeting was the senator’s fifth town hall meeting that day. While someone half the senator’s age might justly find such a schedule grueling, Grassley seemed animated in dialogue with citizens, and his reasoning was as agile and vigorous as usual.

Grassley has held elected office at the state or federal level continually since 1959.

He just completed his first year as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the first non-lawyer in U.S. history to chair that august body. At the time he assumed the chairmanship in January 2015, doubts were expressed — mainly by non-Iowans — about his competence for the position, but the doubters have now fallen silent.

“The fine points of the law are something I’m not up on because I didn’t go to law school,” Grassley said Thursday. “But for the basic policy, there’s no difference. If you’re arguing broad policy — not hair-splitting, what this word means versus what that word means — I can keep up with anybody.”

But can anybody keep up with him? Grassley was named the hardest-working member of Congress by The Hill newspaper in 2010, and he does not look to have slowed down since then.

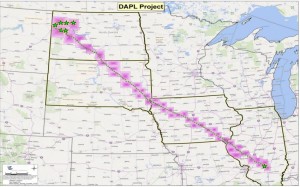

Grassley’s first Woodward question came from a citizen who asked his view of the Bakken pipeline, the proposed $3.7 billion pipeline project that would cross Iowa diagonally through 18 counties as it carried crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois for the company Dakota Access LLC. Proponents of the project are sharply divided from its critics.

“The pipeline you’re asking about, there won’t be any vote in Congress on that,” Grassley said. “It’s entirely a state issue, and I don’t take positions on state issues.” He did note his vote last year in support of the Keystone XL pipeline project, a plan to carry diluted bitumen from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, to refineries in Illinois and Texas for TransCanada Corp.

After lengthy environmental analysis of the project by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — interrupted in 2010 by the three-month BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico — President Obama vetoed the Keystone XL pipeline bill last February. TransCanada suspended its permit application for the project in November.

Grassley’s second question dealt with ethanol production and the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), an EPA program mandating oil companies add a set amount of biofuels, such as corn ethanol, to the nation’s gasoline and diesel fuel supplies. About 40 percent of U.S. corn production is currently converted to ethanol and used as a fuel additive, and the program provides a price support for corn that Iowa agribusiness depends on.

Grassley’s second question dealt with ethanol production and the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), an EPA program mandating oil companies add a set amount of biofuels, such as corn ethanol, to the nation’s gasoline and diesel fuel supplies. About 40 percent of U.S. corn production is currently converted to ethanol and used as a fuel additive, and the program provides a price support for corn that Iowa agribusiness depends on.

In June the EPA recommended reducing the RFS ethanol requirement from 2015’s 14.3 billion gallons to 13.8 billion gallons in 2016. Grassley said he joined with other Midwestern lawmakers to lobby the Obama administration, and they successfully restored the ethanol standard to 14.2 billion gallons.

Grassley said the EPA exceeded its authority by lowering the standard and is authorized only to raise it.

“I don’ think they have the authority to do it,” he said, “but we can’t get legislation passed to override them. Maybe a court case will say they don’t have the authority to reduce it, but they have the authority to increase it.”

He said even a small cut in the RFS will discourage the infrastructure investment necessary to permit increasing the standard ethanol content of gasoline from E10 to E15, that is, from a 10 percent mixture of ethanol in gasoline to a 15 percent mixture.

“It is isn’t just that they cut it back a couple of hundred million gallons,” Grassley said. “Under the law of 2007, we have a restriction that no more than 15 billion gallons can be made from grain, so over 15 billion gallons is going to have to be corn stalks and corn cobs and switchgrass and a whole bunch of other stuff. In order to get to E15, you’ve got to have a distribution system, separate pumps and stuff like that. What the EPA is doing isn’t just cutting back 200 million gallons. They’re discouraging capital investment by filling stations to put in E15 pumps, which you have to have when you start getting ethanol from the cellulosics.”

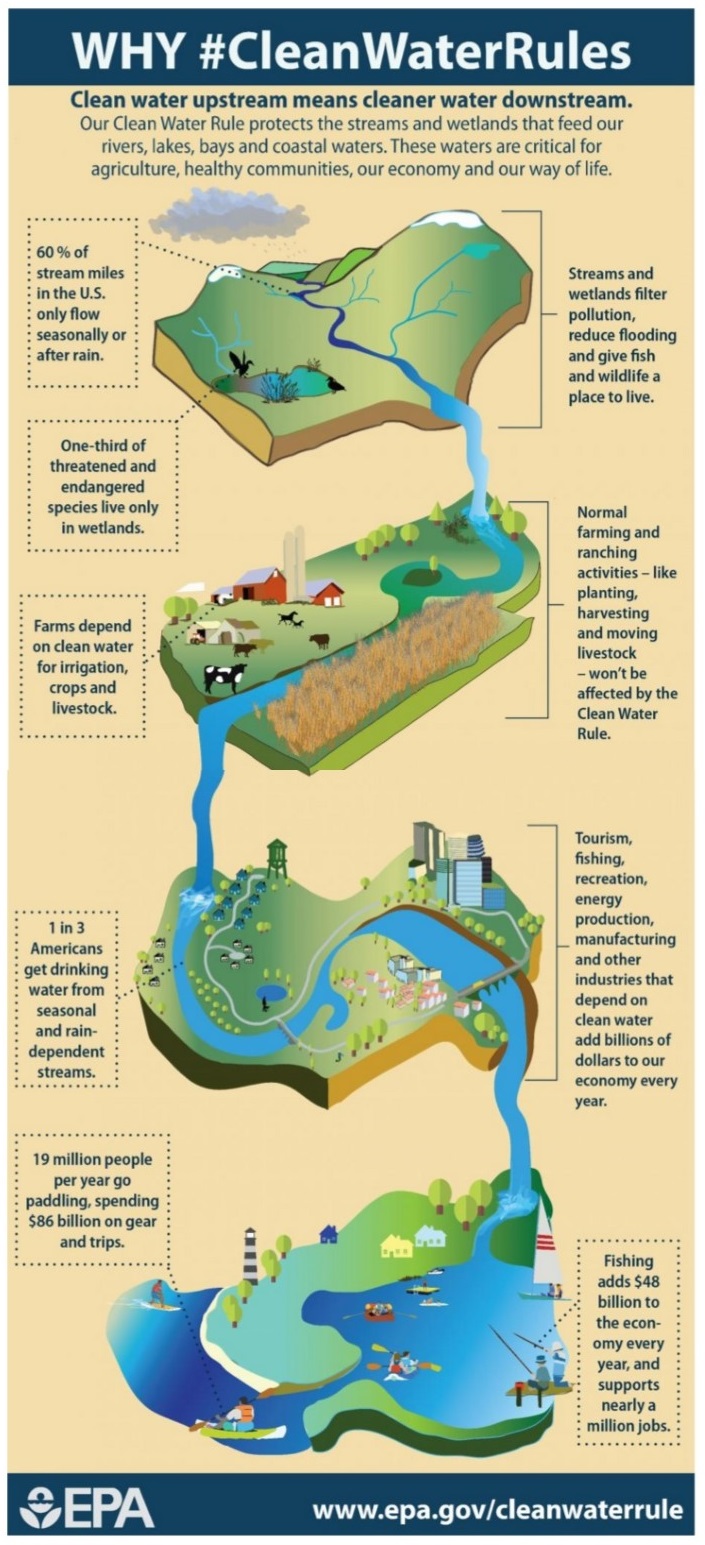

The topic of the EPA’s exceeding its authority continued in Grassley’s answer to a question about his position on the agency’s Clean Water Act (CWA) and its new rule governing the waters of the U.S. (WOTUS).

The topic of the EPA’s exceeding its authority continued in Grassley’s answer to a question about his position on the agency’s Clean Water Act (CWA) and its new rule governing the waters of the U.S. (WOTUS).

Recent efforts by the EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to define more clearly the jurisdictional extent and authority of the 1972 CWA, particularly the meaning of the phrases “navigable river” and “waters of the United States,” led the agencies to issue a rule in 2014 clarifying the extent of federal authority over the environmental quality of upstream waters.

At the same time, the agencies released a so-called interpretive rule that reduced from 160 to 56 the number of routine farming practices exempt from CWA permits. The remaining 56 exemptions were also changed from subjects of hitherto voluntary compliance to ones only exempt if they meet certain technical conservation standards of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

Industry reaction to the rule changes was swift. “Howls of protest have followed,” ag writer Boer Deng wrote at the time in the journal Nature. “Farmers are freaked out.”

Farm groups, led by the American Farm Bureau Federation and the American Farmers and Ranchers Association, pushed back hard against both the EPA’s narrowed definition of normal farming practices near wetlands and proposed changes to NRCS enforcement protocol. They described WOTUS as a “land grab” and mobilized their members so well the EPA withdrew the rule last February under pressure from Congress, particularly from Grassley.

“I don’t understand where EPA authority would end regarding U.S. waterways,” Grassley said last March at the industry-sponsored Iowa Ag Summit in Des Moines, calling WOTUS “a very big threat” to U.S. agriculture. In November he called WOTUS “the biggest power grab of any bureaucracy that I can think of in my time in the Senate.”

Addressing WOTUS on his website, Grassley said, “Congress needs to apply the brakes when an unelected bureaucracy rams through regulations that do not reflect the consent of the governed or uphold longstanding constitutional principles that guarantee the states’ role in our federal system and individual rights regarding private property.”

The tenor of Grassley’s remarks in Woodward was similar. He seems to see WOTUS not as a scientific effort by the EPA to ensure the public a clean water supply by preventing pollution at its sources — in streams, creeks and wetlands — but as an executive agency’s power play for extending the reach of its bureaucratic empire into every wheel rut and barnyard puddle in Iowa.

Grassley explained to the Woodward Lions: “Because bureaucracies are always looking for an angle to get their oar in and get more power, EPA decided, ‘Well, we have a responsibility, since Congress isn’t doing it, under the Clean Water Act to define navigable river.’ Guess what they’ve done. They’ve defined it so that if you look at the Farm Bureau Spokesman, you’ll find a map from a few months ago that said 97 percent of the land in the United States is affected by this new definition of a navigable river. Even places you can’t launch a canoe is a navigable river, and then within 1,000 feet of some place like that is a navigable river. So the Farm Bureau — and the only reason I quote the Farm Bureau is because it’s the only place where I’ve read people have done a legal analysis of what the new definition of navigable river does — but besides the fact that 97 percent of the land in Iowa and I suppose a lot of states in the Midwest, it also affects, according to the Farm Bureau, certain farming operations. If you use a subsoiler, then maybe you can’t use a subsoiler. If you use a new equipment called a ripper, maybe you can’t use a ripper. So what are we getting into here with this power grab? It’s a way for the government indirectly to control more things.”

Grassley described legislative efforts he has made in collaboration with Iowa’s junior senator, Sen. Joni Ernst, to stop WOTUS and curb the EPA, but these tactics have so far had limited success.

“We only got about 54 votes to bring it up, to rewrite the statute so that EPA doesn’t have this authority,” he said, “but even if we’d have got to 60 votes, the president probably would have vetoed it. And we were hoping to get an amendment on the appropriations bill saying none of the money in the EPA appropriations bill could be used to carry out WOTUS. And so we’ve finally been saved at least temporarily by three courts saying that the EPA overstepped its legal authority to write regulations. So it’s held up now nationwide, not just in the states that have filed suit. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals has put an injunction against it across the entire country until the case is heard by the district court. So it’s not applicable right now, but it’s sitting there, and just as soon as some judge says they can go ahead, they can go ahead. But I think eventually the Supreme Court’s going to have a final say on it.”

While it is hard to compromise with a power-hungry executive agency, Grassley struck a conciliatory tone of the kind usually heard from Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad and Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey when they discuss state-level efforts to improve Iowa’s water quality, which is the worst in the U.S.

“Everybody agrees that Iowa has to do more to clean up its water,” Grassley said, “but already we have a voluntary thing put in place. We’ve even had an EPA director out here, not this one but the previous one, at the state fair maybe two or three years ago. They had a forum on this. She said she thought the Iowa plan would do the job. So that’s kind of where we are. I gave you a long answer. I’m sorry.”

Grassley answered more briefly questions on the length of Congressional sessions, on his choice for the Republican presidential nomination, on possible limits to campaign spending, on his first year as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee and on the high costs of prescription drugs –“You’re the third person to ask me that question today in a town hall meeting” — but then someone asked whether the EPA should be abolished, as Ernst has recommended.

“The best chance you’ve got is putting some restrictions on them,” Grassley said, “repealing some of their power. We’re making all their regulations go through Congress before they go into effect. That’d be the best thing to do not only for EPA but for everything. See, agencies can’t write regulation unless there’s some authority in the law that Congress gives them to write regulations, but then they always have a tendency to stretch that power just as far as they can. WOTUS is a perfect example of stretching it. In fact, the courts say they didn’t even have the authority to do it. You get the idea. Even if they had some authority, they’d still probably go further than they should.”

Grassley said he would like to see Congress given a kind of veto power over executive-branch regulation so that regulatory zeal in the cause of clean water, for example, could be tempered by Congressional respect for private property and states’ rights.

“There’s some reason for Congress to delegate some power,” he said, “like scientific stuff, you know, or things that might change on a fairly regular basis that Congress can’t keep ahead of. But we have, in fact, delegated over the decades, most of it since the 1940s, too much power and probably still are delegating too much power. So then when the Constitution says: The power to write legislation is with the Congress, no place else, but there may be some reason to delegate it, then there’s this bill that goes by the acronym REINS (the Regulations from the Executive In Need of Scrutiny Act). It works like this — and the House has passed it several times, but the Senate has not been able to get the 60 votes to get it out. If we did, the president would veto it. But if we get another president and a Senate the way it’s made up now, we might be able to do it — so these regulations that are written would have to come to Congress for us to actually approve before they could go into effect. So if there’s a rationale for delegating some power to the executive branch to write regulations, because maybe Congress, you know, can’t specifically write that much detail into law, then whatever they write brings it right back to the legislative branch that delegated it in the first place for us to make a final decision: Are they writing the regulation according to our intent of the law? Whereas now, like I said, they’ll stretch it, and if you can’t get a Congressional veto, if you can’t rewrite the law, and if you can’t get an amendment on the appropriations bill to not fund it, then your only hope is the courts. So these things — like we talked about, Waters of the U.S. — that would never get through Congress if that regulation had to come back to us.”

In the absence of regulation, the greediest among us make the rules. . . . Big Ag has joined hands with Big Government to screw little you and me. If we don’t stand up to this government-agricultural juggernaut, we won’t have a state suitable for our kids to live in. We have to push back at the voting booth. There is one good and one very good candidate running against Grandpa Grassley. It’s about a decade past time for him to go.

Unfortunately, Grassley perpetuates the myth that area producers are changing their farming techniques to lower nitrate pollution caused by field tile drainage systems that landowners have installed over the years. Big Ag knows if they offer enough incentive, they can get a professional to repeat their mantra just like this doctor https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovKw6YjqSfM. Bill Stowe is right. The way to stop nitrate pollution is to make the landowner responsible for the pollution and held accountable for what is discharged from their drainage system. –Ed Jeffress, Madrid

Re WOTUS – It’s really a shame that Grassley can’t see beyond his support for the farming industry to support the need for clean water for a third of the country’s population. Yes, I get that Grassley represents farmers in Iowa, but he represents a whole lot of others in Iowa – like me – who support sustainable farming practices that don’t pollute and who want clean water.

The EPA wrote these rules to clarify the murkiness caused by two court rulings on the Clean Water Act. They didn’t overreach, as the industry claims. Farm Bureau responded with a lot of nonsense and misinformation in order to create widespread opposition to it. Industrial agricultural practices have to change and water quality – and the subsequent health of Iowans – have to come first before corporate profits. The industry is acting like a spoiled child throwing a tantrum because it can’t get its way.

Earth to Chuck: “The waters are poisoned! The river otters and dragonflies didn’t do that. Children wading in the creeks didn’t do that. Guess what, Chuck? Your industrial-agriculture friends spewed out the pollutants.”

Note how cleverly and automatically Grassley uses the term “bureaucrats” in his folksy delivery. Were the members of the Woodward Lions Club fooled by Chuck? Ernst and Grassley use “bureaucrats” as a ruse to discredit government and university scientists who were hired to protect public health and regulate pollution by using . . . science. Science is governed by verifiable proof, reliable physical data and probability curves that, for example, show confidence levels of the measurable data sets. Perhaps that is just too much information for Iowa’s senators to comprehend?

The criticism of “bureaucrats” is a construct of politicians owned by polluting industries. Put another way, their souls are owned by the devils poisoning Iowa’s surface waters. When I worked for the Iowa DNR regulating petroleum companies, I used very precise chemical analysis to determine that water and soil was polluted by petroleum operations, and the polluter had to pay to clean up their mess. Now, industrial agriculture must clean up their messes, too. Start by holding them responsible for wastewater treatment as we do municipal wastewater treatment facilities like the Des Moines Waste Water Reclamation Agency. Pig sewage is still sewage, even if it is linguistically cleansed so factory hog farms are permitted to spew it — untreated — on fields. If I emptied out my septic tank onto my neighbor’s lawn, I’d be fined, possibly jailed.