My name is Amanda Howard, and I have a 16-year-old daughter named Abby Howard. I want to talk to you about pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in the hope that it makes everyone more aware of the signs.

Abby was born a happy and healthy baby Sept. 14, 2004. My OB didn’t notice any issues with her, and her vitals all looked normal. We were discharged home a few days later.

When Abby was 3 months old, she got her first suspected upper respiratory infection, which required nebulizer treatments around the clock and steroids, but a week later she was back to being a happy, healthy baby. This continued for several months as she would get sick but snap out of it a week later.

Then in May 2005 things changed. Abby started refusing her bottles. She would scream if she was laid on her back. I could only get her to sleep by sitting in a chair and rocking her but every time I mentioned it to my pediatrician, he said it was colic.

Prior to Abby’s crashing, I had her in the ER and my pediatrician’s office very often, but they all missed it. The day before Abby crashed, I took her in again and demanded admission. Abby was finally admitted that night into our local hospital, with the plan of a chest x-ray the next morning, but my pediatrician made a point of telling me that although I was overreacting, he would admit her so he could run tests.

The next morning, Abby was admitted, and I ran home to get breakfast while she had the test. Shortly after I arrived home, the pediatrician called to tell me Abby’s lungs were full of fluid, and she was being taken by ambulance to Children’s Hospital and Medical Center in Omaha.

He told me to get there now.

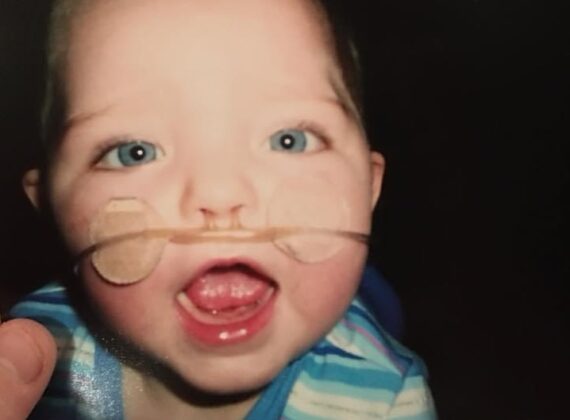

Once the ambulance arrived, I found Abby hooked up to many monitors, and they told me she was very sick. Once at Children’s, we were admitted directly to the fourth floor. A hour late, her pulmonologist decided to order a CT scan of her chest and when Abby came back upstairs, a rapid response team was called.

I will never forget how quickly everyone was moving or how the ICU doctor picked her up and ran down to second floor. Once there, he asked us to sign papers so they could intubate. I signed the papers, and we were kicked out of the room for what seemed like hours. When we were eventually let back in, Abby was receiving medications to sedate her, and she had many doctors around her.

The pulmonologist came in shortly afterward, introduced himself and explained that he wasn’t sure what was wrong but that Abby was very sick. He said he would figure it out.

I remember later that night, as I was watching TV, Abby’s alarms started blaring, and once again people swarmed into the room, and a code blue was called. I was again kicked out, and they drew the curtain. Abby was down for what seemed like forever.

They got her back, but the ICU doctor wasn’t too hopeful that Abby would pull through. We had many doctors in and out, between oncology, GI, genetics, and so on, but Abby just got sicker, and they all said that they were sorry but it wasn’t on their end.

A few days later, I came in one morning after going home and sleeping, and Abby was puffy everywhere. She had many more machines than when I left. I asked the nurse if she was all right, and she grabbed my hands and said let me get the doctor. The doctor asked us to follow him to the consultation room, which we did.

In there I was met with pulmonary, a social worker, a priest, the ICU doctor, and they all said the same thing: your daughter is dying. She had suffered two codes already, and they were sure if there were one more, then they couldn’t get her back. I asked if she was in pain, and they said, no, that they had that handled. They wanted me to sign a do-not-resuscitate form so they could remove the breathing tube, but I refused, and we fought.

Abby was eventually diagnosed with PAH secondary to an unknown lung disease. In November 2005, they believed Abby’s best chance was a double lung and heart transplant, so a referral to Texas Children’s Hospital was in the works. In March 2006, the day before we were to leave for Texas, the cardiologist decided to wait on the surgery because her heart was looking better.

Fast forward to August 2008, and Abby was declared healthy. Pulmonary dropped us, and cardiology moved us out to five years. Then our world crashed again Aug. 31, 2017. I remember her cardiologist coming in and looking sad and asking weird questions as he drew Abby’s heart and a healthy heart.

Our daughter was once again fighting for her life. She was pulled from all activities that required exertion, and tests were scheduled.

On Sept. 13, the day before her 12th birthday, Abby had a stress test that once again resulted in a crash, and a code blue was called again. I remember dropping to my knees as her cardiologist came running down the hallway.

Abby was officially diagnosed with PAH in October 2017. She was put on full-time oxygen, and harsh medications were added.

Please know the signs and symptoms so it doesn’t get as bad for your loved one as it did for my daughter. Abby was having chest pain in PE class. She refused to walk to the park that summer of 2017, and we thought it was her age but later found out she got tired and short of breath. Abby had occasional dizziness. These are all the symptoms of PAH that we ignored.

My daughter has a rare disease, but a simple echo would have picked it up sooner. Abby has more lung damage as a result of having gone untreated.

Her team refers to her as an amazing kid who seems healthy on the outside, but the inside is fighting a battle. Her lungs look horrible on paper, but you would never know it. She doesn’t let this disease win. Abby has officially been diagnosed with idiopathic PAH, and the idiopathic label means her team can’t find what caused it.

Abby suffers with fluid retention, tiredness, shortness of breath, occasional chest pain, red face, pain, upset stomach and other symptoms, but she is alive. To keep Abby alive costs about $30,000 a month, but she is worth it. These medications are slowing down the progression of this disease.

The sooner this disease is diagnosed, the better the chances the patient stands of survival.