In a replay of the same futile gesture they made in June 2008, the Dallas County Board of Supervisors voted Thursday to advise regulators at the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to reject an application for a construction permit seeking to double the size of a Dawson hog confinement.

The board’s decision came at the end of a two-hour public hearing and after weighing public comments from about 35 citizens, both backers and opponents of the proposed expansion of the concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) in Dallas Township.

“I’m really surprised,” said Stacy Hartmann of rural Minburn, chairperson of Dallas County Farmers and Neighbors, the citizen-action group leading the opposition to the expanded confinement. “I’m happy with the vote. I’m glad. I feel like the supervisors made a reasonable decision and are actually listening to the concerns of the residents of the county.”

But as in 2008, the supervisors’ latest resolution will likely prove to be little more than an empty gesture.

“Had we not done this,” Hartmann said, “had people not come and put all this time and work into this, it would have gotten passed tonight. And it might still go up. It probably will.”

The supervisors chose — in a two-to-one vote — to withhold approval from the expansion application on the grounds of “vagueness” in its answers to questions posed in the master matrix, a kind of CAFO scorecard.

The master matrix is a CAFO scoring system adopted by the DNR in 2004 after prolonged wrangling in the Iowa legislature. It is a compromise instrument hammered out between agribusiness lobbyists, who resist on principle all regulation of crop and livestock production, and environmentalists, who claim the master matrix is a sham form of local control that sacrifices Iowa’s water, air and soil quality on the altar of commodity-producer profits.

With that controversy still simmering, the master matrix has been adopted by 88 of Iowa’s 99 county governments, including Dallas County. According to DNR policy, “Counties that adopt the master matrix can provide more input to producers on site selection, the proposed structures and proposed facility management.”

The master matrix awards points to a CAFO based on its estimated impact on air and water and its likely effects on the quality of community life. For example, a CAFO earns more points the farther away it is built from a river or creek or from a church or school.

A CAFO’s siting or placement is the most crucial factor in a master matrix score, with additional emphasis placed on the design of the manure containment structure and on the producer’s plans for disposing of the manure.

The 880 points in the master matrix score sheet are spread over 44 questions, and a proposed CAFO must earn at least 440 points, or 50 percent, in order to pass. There are also minimum point requirements in each of three categories: air, water and community.

If a CAFO application earns a passing score on the master matrix, the DNR routinely issues it a permit. Withholding it would exceed the DNR’s statutory authority, according to the Iowa legislature’s Administrative Rules Review Committee, which has deemed the master matrix “the exclusive mechanism for the evaluation and approval of an application for the construction or expansion” of a CAFO.

A local case in point

Thursday’s public hearing in Adel concerned a CAFO construction permit sought by Kent Scheib of rural Perry. Scheib is president of Victor Allas LLC, a CAFO company with a 3,600-head hog confinement lying a little southwest of Dawson in Dallas County and an 8,000-head confinement a little southeast of Jamaica in Guthrie County.

The CAFOS are about two miles apart from each other. Scheib wants to double the size of his Dawson CAFO, bringing it up to 7,200 head of hogs. He owns the building, but Cargill Pork owns the pigs. The nation’s eighth-largest pork producer produces most of its piglets at a 21,500-acre sow facility near Dalhart, Texas, from where they are shipped to contract finishing CAFOs in Iowa, such as Scheib’s.

An applicant calculates his own master matrix score, and Scheib’s earned a score of 540 out of 880 or 61 percent, which exceeds the minimum score legally required in order to satisfy DNR regulations and guarantee routine DNR approval.

Because a CAFO construction application, including its master matrix, is a complicated document, a pork producer usually hires a technical expert to fill it out for him. Schieb hired Pinnacle, an agronomic consulting firm specializing in environmental and regulatory compliance. The Iowa Falls-based company produces many of the master matrices and manure management plans for CAFO applications in Iowa and helps steer them through the DNR process.

Pinnacle President Kent Krause joined Scheib at Thursday’s public hearing and answered technical questions raised about the application’s master matrix score and its manure management plan.

The Scheib family is well known and beloved in Perry. Kent Scheib has farmed for more than 40 years with his brother, Chuck, who recently retired. Their Century Farm of 700-plus acres has been in the family for 132 years.

“These things (CAFOs) are environmentally friendly.” –Kent Scheib

Kent Scheib’s nephews, his brother’s sons, are young men who say they want to carry on the family business. Joe Scheib, 32, lives in Perry with his wife and children, and Dane Scheib, 34, lives with his family at the “home place,” the farmhouse at 16446 B Ave. where Kent and Chuck Scheib and their siblings grew up and where they helped their father raise hogs in a way now rarely seen.

The house on B Avenue lies about one-third of a mile south of the confinement on 160th Street they want to expand, making Dane and his wife and daughter the CAFO’s nearest neighbors.

Dallas County Board of Supervisors Chairperson Brad Golightly of rural Perry laid out the ground rules for Thursday’s public hearing, first opening the floor to the Scheibs, who explained their reasons for seeking to expand their operation.

Krause followed with a brief explanation of the master matrix score, and the Dallas County Planning and Development Department then reported on its review of the application and confirmation of Pinnacle’s master matrix score. The public was afterward invited to make three-minute comments.

Doubts raised about master matrix score

About 25 people rose to urge the supervisors to reject the application. The speakers touched on the common themes often heard in such meetings, warnings about the general threat CAFOs pose to public health, water quality, property values and long-term agricultural sustainability.

The opponents came mostly from Dallas County, with a sprinkling from Boone and Polk counties, and they included retired DNR officials, academics, farmers and members of citizen-action groups.

The opposition was led by Hartmann and other members of Dallas County Farmers and Neighbors, a citizens group working to stop the growth of CAFOs and promote humane livestock production.

Hartmann noted Dallas County is already home to 500,000 confined animals. She said the Scheib expansion would add another 1.9 million gallons of “untreated waste” to the 30 million gallons already produced annually in Dallas County’s 29 CAFOs, of which 22 are hog confinements.

“In our review, we found 165 points that should be deducted.” –Stacy Hartmann

Greene County, in contrast, contains 81 hog CAFOs, Boone County 34 and Guthrie County 29.

Hartmann disputed the validity of the 61 percent rating on the Pinnacle-scored master matrix.

“As usual, a failing grade by all accounts in the real world but not for the matrix,” Hartmann said, “for which less than 40 percent of the questions were responded to and which takes nearly all its points from the most absurd questions and arbitrary distances and none from those factors which would improve the quality of life for area residents. In our review, we found 165 points that should be deducted.”

Another Dallas County Farmers and Neighbors member, Jan Danilson of Woodward, raised several technical objections to the accuracy of the Scheib master matrix. Danilson is also a member of the Boone County Planning and Zoning Commission, and she challenged the Dallas County Planning and Development Department’s review of the Pinnacle matrix score.

“I’ve looked at the matrix also,” Danilson said, “and I agree with Stacy that there are quite a few areas on there where points should be deducted. I’ve looked at other matrices also in other counties, and it looks like the Pinnacle company has a tendency to copy and paste from one to another.”

Samuel Larson, senior planner with the Dallas County Planning and Development Department, defended his department’s review of the application.

“We don’t deal with anything involving agriculture because agriculture is exempt from zoning in the state of Iowa,” Larson said. “However, the board asked our department to do the reviews, and so I’ve done a thorough review of the application materials. I’ve done extensive mapping. I’ve visited the site and driven through the neighborhood twice, looking to see if there’s anything they might have missed that would somehow change the score, and my review echoes their review. I recommend the same score that they score themselves at: 540.”

Iowa Farmers Union board member Rick Hartmann of rural Minburn also called Pinnacle’s master matrix score into question.

“Contractors are hired to put together the matrix,” Hartmann said. “It’s pretty much a sham operation anyway. It’s a cut-and-paste job, with kind of C-minus material in there. We could pay attention to it. It could be done right.”

Pressing his case, Hartmann cast doubt on the accuracy of another part of the CAFO application, the manure management plan.

“No one looks at them (manure management plans) closely, including the Department of Natural Resources,” Hartmann said. “We’ve got a lot of what’s called double dipping going on. So CAFO A from farmer A and CAFO B from farmer B are claiming on the manure management plans the same fields. It’s even happening in Dallas County.”

Pinnacle’s Krause strongly disagreed with claims his manure plans are shoddy or deceptive.

“The DNR does scrutinize the manure management plans down to every detail,” Krause said. “This manure management plan will be scrutinized by the DNR before they give their final approval.”

“I recommend the same score that they score themselves at: 540.” –Samuel Larson

Hartmann maintained his point.

“The DNR does not scrutinize every one of the state’s 8,000 manure management plans,” he said. “I will give you an affidavit from the DNR stating they do not have the staff, the resources, the money budgeted by the Branstad administration or the time to do so.”

Danielle Wirth, professor of environmental science and policy at Iowa State University and Drake University, supported Hartmann’s claim of staff overload at DNR.

“The DNR does not have the staff to do an adequate job,” Wirth said. “We reviewed manure management plans, mostly done by Pinnacle. We found glaring errors. There were some fields that we found that were not getting the one treatment that the manure management plan allowed, not two, not three, but one had four applications of manure. So I would be very careful about trusting anything that Pinnacle is telling you.”

Questioned after the hearing, Krause and Scheib defended the accuracy of their manure management plan and rejected charges leveled in the hearing.

“That was near slanderous,” Krause said. “We have to keep records for five years. We have to document every field and exactly how many gallons. The manure has to be applied by a licensed applicator. These manure plans are audited at any time on a random basis.”

Scheib explained the appearance of so-called double dipping.

“You have farmers that farm a lot of ground,” he said, “so you might have that field as an option in two or three plans. That doesn’t mean they’re applying to those fields every year. Any field that we haul to has to be pre-approved. It doesn’t mean we’re hauling to every field. So I take all the fields that somewhere in the future I might want to put manure on, and I’ll put them in this plan because I’ll generally move the manure around. So one year it might be on this field and this field, and the next year it might be on that field and that field. If I’m going to put manure on a field or even suspect that I’m going to — I might not ever put in on there but if I think I might — I go ahead and do the leg work and do the math and get it pre-approved so if, come fall, I decide I do want to put manure on that field, I’ve been pre-approved to go on that field.”

“They make those accusations, and it’s just absolutely not true. It just doesn’t happen.” –Kent Krause

Krause said between 10 percent and 15 percent of Iowa cropland is fertilized with organic fertilizer, such as hog manure. The rest is treated with petroleum-based commercial fertilizers, which are more expensive and completely unregulated by the DNR, he said.

“It’s counter-productive to double apply them,” Krause said. “If you’re saving money by applying manure on that acre, why wouldn’t you apply that over every acre you could instead of double applying? It’s counter-intuitive. They make those accusations, and it’s just absolutely not true. It just doesn’t happen.”

It is uncertain whether it was these or other objections made by the CAFO’s opponents that raised the specter of “vagueness” in the minds of two Dallas County supervisors, but the strategy apparently succeeded in making the master matrix seem dubious.

“We know you’re constrained by the matrix,” Stacy Hartmann said to the county supervisors. “You did not design it. You’re not to blame for it. We get it. We do ask that you scrutinize it carefully and consider our submission. Demand that it be more thoroughly filled out. Too much is at stake to tolerate vagueness and sloppiness. Or deduct no points. Call it what it is: a bad idea. Deny it, and gain two months to prepare for an EPC hearing.”

Do CAFOs threaten human health, water quality, home values?

Beyond challenging the technicalities of the master matrix, opponents of the expanded CAFO operation gave the usual litany of dangers CAFOs supposedly pose. These claims are alarming in themselves, but they seem to carry no more weight with the supervisors than they do with the DNR. Both bodies know once a CAFO application clears the hurdle of the “exclusive mechanism,” the master matrix, permission follows automatically.

Dr. Cheryl Standing, a Des Moines pediatrician who lives on a Century Farm north of Earlham in Dallas County, told the supervisors about evidence of negative health effects associated with CAFOs, including asthma, microbial resistance to antibiotics and hormone and antibiotic contamination of the water and meat supplies.

“From my standpoint, I have serious concerns about the public health issues in our state and in our county,” Standing said. “As the people that hold the power and the intellect and look at the facts, we should really look at all the facts and review this and do the right thing, the right thing for the next generation.”

The topic of Iowa’s water quality has lately been much in the news. As several speakers at the public hearing noted, Iowa has the worst surface water quality in the U.S. Fully 44 percent of the state’s water bodies are polluted, according to the DNR’s recently released list of 572 “impaired” waterbodies, which shows a 19 percent increase in the number since the previous survey in 2012.

The Des Moines Water Works’ lawsuit against drainage districts in three northwest Iowa counties over nitrate pollution has also brought the issue of water to the fore. The Des Moines Register recently reported water supplies in 60 Iowa towns have nitrate contamination the towns cannot afford to remove.

“What we’re doing is we’re poisoning ourselves. We’re poisoning the water that we drink.” –David Hance

Addressing the proposed Scheib CAFO expansion’s relation to water quality, David Hance of Ankeny, a member of the Raccoon River Watershed Association, urged the supervisors to reject the expansion application and stop all further CAFO construction in Dallas County.

“The nitrates from this particular hog confinement will in time end up in the Raccoon River,” Hance said. “We can’t afford to do this right now. It’s poisoning us.”

The Scheibs’ Dallas County CAFO lies in the Fanny’s Branch watershed, a subbasin of the North Raccoon River watershed.

Hance said Thursday’s measures of nitrate contamination in the Raccoon River, from tests taken at Jefferson and Van Meter, show levels exceeding U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards for safe drinking water.

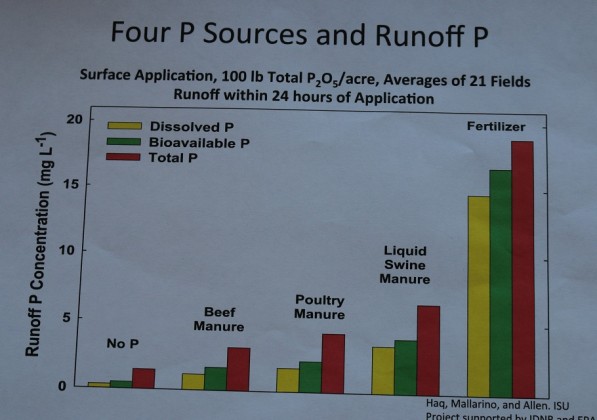

“What we’re doing is we’re poisoning ourselves,” he said. “We’re poisoning the water that we drink.” Hance also mentioned an algae bloom now occurring on the west side of the Mile-Long Bridge in Saylorville Lake. According to scientists, algae blooms are caused by excess phosphorus, which like nitrate is a nutrient entering Iowa’s waterways through farm fertilizer runoff.

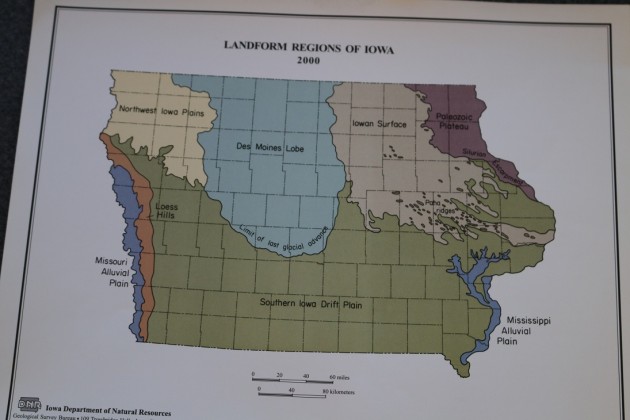

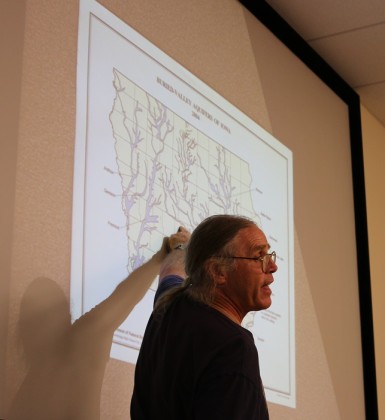

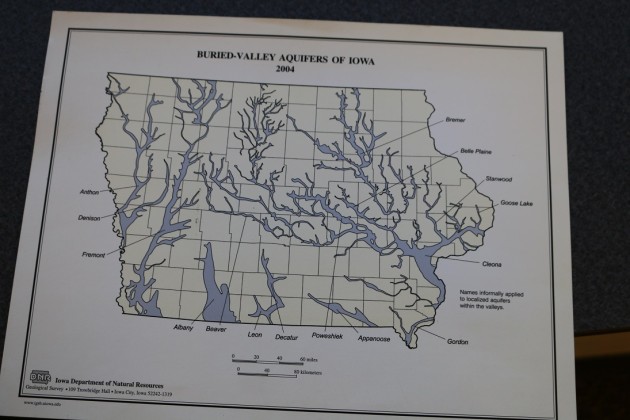

But contaminated surface water is only part of the picture, according to Don Wirth, anthropology instructor at Drake University. Wirth said the Scheib CAFO is “dangerously close” to the Beaver Aquifer, which supplies well water to Perry, Woodward and the Xenia Rural Water District. He described the area’s complex subsurface water system of ponds, streams and aquifers.

“Most people, when they’re talking these CAFOs, they’re asking, ‘Where are the streams? How many feet are we away from the streams?’ My point is it isn’t just the surface water. It’s the subsurface water, and we’re completely missing it.”

Issues of country living and property values were also raised by opposition speakers at the hearing. Mark and Ann Grittman recently bought an acreage near Dawson for the sake of “quality of life.” Mark Grittman asked the Dallas County Board of Supervisors about their commitment to their own mission statement as it appears on the county’s website.

“You talk,” Grittman said, “about the mission statement of the board of supervisors: ‘As stewards of the public trust and resources, the board of supervisors will strive to maintain and improve the quality of life for the citizens of Dallas County.’ Besides the Scheibs here, I guess I’d ask the board, Who does this benefit? How does this help the other citizens of Dallas County?”

Grittman said the website also mentions a Dallas County Master Plan, and he asked the board whether they really have a coherent plan for growth and development.

“I think we all deserve to know how many CAFOs, how many more hogs are going to move into this county in the next 25 years.” –Mark Grittman

“Looking at growth projections in the county overall,” Grittman said, “roughly 75,000 live in the county now. By 2040, this projection is nearly 160,000 people, granted, a lot of those on the eastern half of the county. Today we have roughly 88,000 hogs in Dallas County, and my main question really is: how many hogs will there be in Dallas County by the year 2040? I don’t know if anybody has that answer. We should be able to calculate that.”

There are currently 17 towns in Dallas County and 28 CAFOs. Grittman displayed a county map, with black dots for the towns and red dots for the CAFOs.

“Each of those black dots has a sewage treatment plant for human waste, and each of the red dots has nothing,” he said. “It goes on the ground. If we had human sewage on the ground, it would make the national news. If sewage from a CAFO goes on the ground, nobody knows. Only the people around that area care.”

Grittman encouraged the board to make long-range plans for managing the rural-urban mix in Dallas County.

“What is the long-term plan for CAFOs?” he said. “I’m definitely interested in this CAFO in particular but in the long run, in the interests of the people who are here now and the 85,000 residents who are projected to move into Dallas County, I think we all deserve to know how many CAFOs, how many more hogs are going to move into this county in the next 25 years.”

“CAFOs are what we have to have.” –Linda Brewer

Though far outnumbered, defenders of the Scheibs also had their say at the meeting. The mother-daughter team of Linda Brewer and Emily Wynn, CAFO owners near Dallas Center, made statements supporting the Scheib expansion and more broadly defending the methods of modern livestock production.

“I’m a mother. I’m a farmer. I’m a nurse,” said Linda Brewer. “I understand our system. I understand our concern about bringing our children back to the farm. That’s what we did when we initially put up our CAFO. We were thinking longterm about what we can do to get our children back into agriculture.”

Sounding a little like former U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Brewer said there is no alternative to CAFOs.

“CAFOs are what we have to have,” she said. “We’re sitting here looking at people with computers. Should we not have those? Farming needed to evolve. We cannot go back to each of us having 10 sows and thinking we can make a living farming.”

Reserving their deliberations for the end of the meeting, the Dallas County Supervisors received all the public comments in silence.

What’s past is prologue

Hog confinements are highly controversial. That is not news to most Iowans. Dickinson County recently released the results of a one-question survey it conducted among the other 98 county boards of supervisors in Iowa, and they show just how controversial CAFOs are.

Dickinson County asked the other county supervisors to say whether they favored, opposed or had no opinion about the question: “Should the existing Master Matrix system be repaired to include more local control for counties to preserve and protect the natural resources within their counties?”

The results showed county leaders almost as sharply divided in their opinions about CAFO control as Iowa’s population as a whole. Of the 64 county boards responding, 23 said they favored repairing the master matrix (16 unanimously), 19 opposed changing it (17 unanimously) and 22 had no opinion (12 unanimously).

The Dallas County Board of Supervisors did not respond to the Dickinson County survey.

Most reasonable people admit agronomy and soil science are highly technical subjects. Animal husbandry is also a very precise science. You do not need to look too closely at the current state of swine genetics to realize we put a lot more care into the breeding of our hogs than into the breeding of ourselves.

In this as in so many matters, one must rely on the advice of technical experts — not so much for truth with a capital T as for rational judgments based on the most complete and current information available. Our knowledge is always imperfect because always incomplete, leaving our scientific opinions always more or less provisional and always subject to revision in light of new information.

Today’s truth is the best we have. Our limited knowledge can make decisions difficult and sometimes even dangerous but as Baroness Thatcher said, “There is no alternative.” These complexities make many county boards of supervisors only too happy to leave CAFO decisions to state-level technocrats in the DNR.

The Dallas County Supervisors are no strangers to contentious CAFO applications. In 2008 the board also voted — unanimously in that case — to recommend denying two construction permits for a 14,400-head CAFO operation planned by Robert Manning of Granger.

The board was chaired at the time by Bob Ockerman, with Brad Golightly and Mark Hanson also supervising. Just as today, Senior Planner Larson reported that the county’s review of the matrix tallied exactly with the applicant’s.

According to DNR policy, “While all counties may submit comments to the DNR during the review process for permit applications, counties that adopt the master matrix can also appeal approval of a preliminary permit to the state Environmental Protection Commission” (EPC).

“Well, half those trees are now dead.” –Ray Harden

When the DNR under Richard Leopold approved the Manning permits contrary to Dallas County’s recommendation, the supervisors appealed the decision to the EPC, then chaired by David Petty of Eldora.

Through the prodigious rhetorical powers of Dallas County Attorney Wayne Reisetter and possibly owing to the righteousness of the cause, the EPC was persuaded to make an unprecedented exercise of its statutory power. It overruled the DNR and denied Manning his CAFO permits.

But the EPC’s six-to-two ruling did not stand long. Within weeks Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller’s office had negotiated a deal with Manning’s lawyers that forced the EPC to reverse its decision and issue the permits in exchange for some minor modifications in the CAFO’s landscaping plans.

Ray Harden of Perry, a member of the state Soil and Water Conservation District Commission for Dallas County, recalled the 2008 turmoil.

“At the time the DNR caved in, Rich Leopold was the DNR head under Iowa Gov. Chet Culver,” Harden said. “He said he got concessions from them: trees. Well, half those trees are now dead.”

Paul Johnson of Decorah, former DNR head and three-term state representative, was an EPC member voting with the majority in overruling the DNR in 2008.

“A lot of these decisions ahead are not going to be fun,” Johnson said at the time, “but we’re going to have to make them to make life better on our land. They’re not made frivolously. To me, good science and common sense said there shouldn’t be a big hog facility on that site.”

“It is what it is”

When no further comments were offered from the public, Supervisor Hanson’s motion to close the public hearing was approved. Dallas County Supervisor Kim Chapman then opened the board’s discussion.

“I think the application is very vague myself,” Chapman said. “I can’t believe the technology isn’t there to address some of these concerns so we can all live together, so you can have your operations, and your neighbors can be happy to live close by you. It’s obvious we’re not there yet. I’m going to move that we reject the application because of vagueness.”

Hanson promptly seconded Chapman’s motion, which was then discussed.

“I’m torn over this issue,” Chapman said. “I’m not an expert. Let me tell you, I have a hard time. When a farmer comes before us, and they say he’s not a farmer — he’s a farmer. He’s trying to do the best he can to support his family. He has sons here who would take over the family business at some point in time. But on the other hand, I drive by them as well from time to time. There is odor. I am concerned about water quality as well. How do we resolve these issues?”

Supervisor Golightly registered his disagreement with Chapman’s motion but joined him in rejecting the claim the Scheibs are “factory farmers.”

“I am in full support of this family and their application because they have followed the rules,” Golightly said. “Some of the rules we can make up ourselves, and some of the rules come down to us from the state or from the federal or whoever they are, but those are our society and what we have to work with and live with.”

Although the Scheibs farm on a massive scale, “in terms of best efforts, best practices, reputation, this family has been there for 132 years,” he said. “If somebody says, ‘These are factory farmers,’ I don’t believe that for a minute. So I do not support the motion that has been made.”

Dallas County Attorney Reisetter offered his legal opinion. He predicted the board’s recommendation to reject the permit application would be disregarded by the DNR unless the supervisors cut points from the master matrix score.

“If you’re looking to be as effective as you can be,” Reisetter said, “if you’re looking for rejection, then you probably should take a look at the scoring and consider how you determine the scoring should be, in your best judgment, to give some effect to any action the EPC will recognize. If you’re recommending approval, then the scoring approves it and it goes forward.”

The supervisors stood by their recommendation to deny the application but left the master matrix score intact, in this way effectively reducing the evening’s events to a spectacle of powerless political theater. Speaking earlier on Thursday, Scheib was also realistic about the ultimate importance of the public hearing and the supervisors’ recommendation.

“The county supervisors basically have zero power,” he said. “Tonight’s just a show because the supervisors can do whatever they want as far as they can try to deny the permit or say we’re not going to do this, and then basically it just bypasses them and goes to the DNR. We have a master matrix in this state, so the DNR’s in control. As long as you’re passing and have enough points on that master matrix, usually you just don’t have any problems. The county supervisors can scrutinize that master matrix and try to throw some points out, but it’s pretty hard for them to do that, I think, when these professional people who do this every day put them together.”

At the same time, Scheib vigorously defended his reputation as a responsible steward.

“I guess I’d consider myself an environmentalist,” he said. “I’m a liberal-leaning Democrat, and I’m an environmentalist. I believe in wind generators and solar panels and doing what’s right for the environment. We’ve put all kinds of terraces out on what most people consider flat ground, and other people don’t do that. We’ve put grass waterways in and CRP buffer strips. These things (CAFOs) are environmentally friendly. I’m going to sit there tonight after everybody’s done talking and, hopefully, quietly and rationally and calmly tell them why these are environmentally friendly.”

Ray Harden of Perry was not prepared to call the supervisors’ actions wholly ineffectual.

“Most people think the master matrix system is not working correctly,” Harden said. “CAFOs pass with too low a score. They even get points for not having had a CAFO in the past. Most environmentalist feel that more safety precautions must be installed and more local control is needed. The only way this can be changed is for the public to object to CAFOs and for county supervisors to vote No in order to make the DNR, the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship and the Farm Bureau come up with a new plan to satisfy the general public and the environmental watch dogs. Currently, there are more than 8,000 CAFOs in Iowa. How many more can the land and air hold? How much more untreated animal waste and hydrogen sulfide gas will go into the water and air before we all get sick? There is a saturation limit somewhere.”

But these are not the kinds of questions posed on the master matrix. Thursday night’s events demonstrated what we already knew: local control of agriculture is against the law in Iowa, although some people at the hearing seemed determined to change that state of affairs, throwing a particular legal challenge in the direction of the Dallas County Attorney.

“These are buildings, not barns, factories, not farms.” –Rick Hartmann

“Hey, get together with some other county attorneys,” Rick Hartmann of the Iowa Farmers Union said. “Let’s turn this around. Let’s start taxing (CAFOs) as industrial. Let’s deny the legitimacy of the matrix. Take it to court. That’s what happens when someone overreaches and shoves things down your throat that they have no business doing. We run this county, not the state executive committee that flies back and forth to China to help out CAFO operators and industrialists. This is our county, not theirs. There used to be lots of independent hog farmers in this county. I still buy meat from them at the Redfield Locker. There’s no reason that can’t happen again. We can have twice as many farmers and a hell of a lot less toxic waste in this county raising hogs. We did it before. We can do it again. Every building you approve, that’s ten farmers who go out of business.”

The county attorney did not opine on the proposal. Similarly, a particular political challenge was reserved for the three Dallas County Supervisors and delivered by the Dallas County Farmers and Neighbors.

“Regardless of what you decide to do tonight,” said Stacy Hartmann, “continuing to approve these CAFOs and hiding behind the claim that there’s nothing you can do, that it’s all up to the legislature is not acceptable to us. It’s bad leadership. It’s bad governance. And it only benefits large corporations and their contractees. This passivity is an affront to those many whose interests — including property values, quality of life, health and natural resources — you were elected to protect. Strategize as a board about what you could do, such as working with the Iowa State Association of Counties to pressure the legislature to strengthen the matrix or to pass local control — something, anything to change the regulatory system that is in direct conflict with your role as county stewards. Dallas County Farmers and Neighbors has done what it can do. The people who will be speaking tonight are doing what they can do. The question now is: as our elected representatives, what are you going to do to stop the expansion of CAFOs across Dallas County?”

Brave words, surely, but as our Tea Party friends never tire of telling us, the government cannot do anything right. And perhaps it is asking too much of our elected officials to stand up and put a little more starch into regulations governing Iowa’s most powerful economic interest: agriculture, with its handmaid the financial services.

Maybe the market will sort it out. Current trends suggest it might. Fast food retailers are more and more taking to selling free-range chicken and gestation crate-free pork. Grass-fed beef is all the rage. Antibiotic-free, hormone-free, organic — these labels are now seen more and more, particularly in trendy urban outlets such as Wal-Mart.

These are orders producers cannot afford to disobey.

If government has been shrunk to a size at which it stands in danger of being drowned in a bathtub — the long-term goal of American zealots like Grover Norquist, Ronald Reagan and their underwriters — then maybe only heroic citizen-consumers can bring about marketplace change by exercising their right to vote in the most meaningful way left to them: with their dollars.

We have 8,000 CAFO’s in this state and only 15 DNR inspectors. CAFO operators can make all the claims they want about their operation, but the general public will never really know. There is no accountability. Every CAFO needs to be permitted and inspected, but Branstad and his cronies at the DNR are making sure that doesn’t happen. Our pork is chuck full of antibiotics and growth hormones because pigs are crammed together in pens that are a breeding ground for the proliferation of disease. Workers wear hazmat suits!